Someone buys an “AI tool” for the company.

They switch it on. They run a few demos. Everyone nods like the future just arrived. Someone says “game changer” and everybody of course claps.

Two quarters later, nothing has really changed.

Work is still messy. People are still busier than ever. The only clear improvement is that there are now more meetings to talk about AI. Plus a new dashboard. Plus a new cost line in the budget that is ashamed of itself and tries to hide.

And in the meantime, everybody is shouting that AI adoption is exploding. McKinsey’s latest global survey says 88% of organizations now report using AI in at least one business function, and also, we’re told the pilot-to-production problem is improving. Bain says more use cases are moving to “production at scale”, with software development leading at 40% of pilots moving to scale (customer service is 32%, for example).

So what’s going on?

Simple. Adoption is not transformation. “We use AI” often means “someone opened ChatGPT twice, created a project and renamed it ‘knowledge management’”. And “moving pilots to production” often means “we deployed it somewhere”… and not “we redesigned the workflow, changed roles, fixed the data, measured end-to-end outcomes, and actually got durable gains”.

McKinsey basically says this too, they say that despite high usage, only about one-third say they’re scaling AI across their organizations, and most are still stuck in experimenting or piloting phases.

So yes, the headlines are true. Adoption is rising, and some pilots are graduating.

But the boring monster under the bed is still there, which is that AI is getting installed faster than work is getting redesigned.

And until that flips, you’ll keep paying for “the future” while you still live in the same old present… just with more dashboards giving you sleepless nights. That’s the problem that I call the AI Productivity Paradox. AI is spreading fast and money is pouring in, but the big productivity numbers somehow do not move much. It looks like AI is everywhere, but not in the results.

And no, this does not automatically mean AI is useless. It usually means we’re doing what we always do which is buying tools, skipping the hard work, and then acting surprised when reality doesn’t clap.

But there’s also an alternative explanation.

That we’re measuring productivity wrong.

I wrote about it as a side-dish in these posts: Empirical reflections on the silent murdering of the workforce via task-level automation by overconfident algorithms causing occupational extinction | LinkedIn and The AI productivity divide | LinkedIn – but in this post I really want to dig deep into what causes this paradox.

So, expect a lengthy piece. Boring, long sentences and difficult words as if it was written by a drunk member of parliament, with lots of graphs and in depth explanations. And if that’s not your thing, wait for next week, because that will be full of tech-smut again.

More rants after the messages:

- Connect with me on Linkedin 🙏

- Subscribe to TechTonic Shifts to get your daily dose of tech 📰

- Please comment, like or clap the article. Whatever you fancy.

The paradox in plain words

The AI productivity paradox is two trends fighting in the same room.

AI adoption is high. Investment is huge. Expectations are loud. And on the other hand, productivity growth is modest and looks a lot like the historical average, with no clear “AI acceleration” showing up in the aggregate numbers.

That disconnect is the whole plot. And I could just have given you the TL;DR and get it done with, but I like to torture my readers..

And the thing is that this is not one single mystery. It’s a stack of mechanisms that reinforce each other, for instance, a time lag, also some cases of bad measurement, shallow AI implementations we don’t see, and humans misreading their own output. Especially the latter.

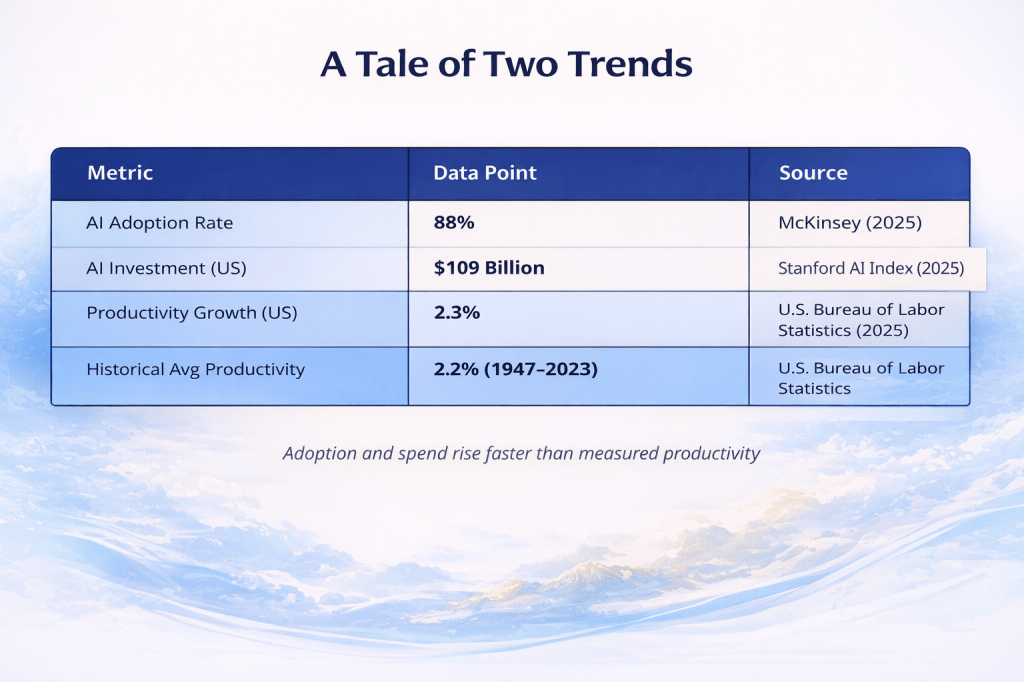

In this table you can see that AI usage is high (88% of organizations reporting AI use), spending is enormous (illustrative headline investment figures like $109B in the U.S.), and yet measured productivity growth sits around the same historical neighborhood (around 2.3% versus a long-run average of ~2.2%). That gap is the whole plot. The inputs and hype signals are quite visible, yet the output signal is calm, and everyone pretends the calm line is just “early days” instead of admitting that value is either delayed, or never operationalized in the first place.

The purpose of the table is not to prove AI does nothing, but to show why “AI is everywhere” can be simultaneously true while “productivity is exploding” is still mostly a bedtime story.

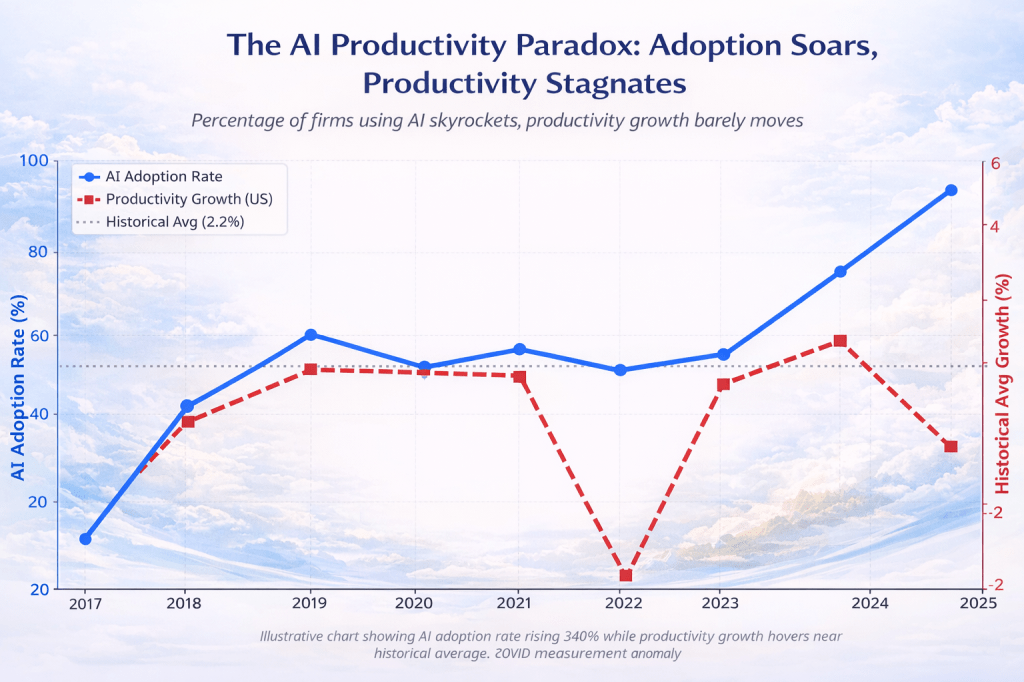

This chart puts two lines on the same timeline and lets them embarrass each other in public. The blue line indicates that AI adoption is rising hard over time, roughly a 340% jump from the early baseline to the latest point. And that is exactly the growth curve that makes executives say “game changer” or “revolution”. But the red line shows productivity growth doing… mostly what it always does, hovering around the long-run historical average (the dotted 2.2% line) rather than taking off like the marketing decks promised.

The point is not that productivity never moves, but that it doesn’t move in proportion to the adoption narrative, which is why this is a paradox and not a victory lap.

The brief weirdness in the middle years simply reinforces the bigger pattern that adoption can surge and the macro productivity line stays normal, and that is because adoption is not the same thing as workflow redesign, and the economy does not award points for installing software.

And now the fun part. The four drivers of the AIpocalypse

The four drivers

So if AI adoption is rising and pilots are “going live,” why does productivity still look like it’s taking a nap in the lactation room?

Because the paradox isn’t one problem. It is actually four separate problems stacked on top of each other, and all are wearing a trench coat, and pretending to be “digital transformation through AI”. The four drivers of this divide, that keep showing up across the industries that I’ve analyzed are,

- a time-lag J-curve

- broken measurement

- lazy work design

- and humans confidently misreading their own speed.

Let’s walk through them, one at a time, like a crime scene tour… investigating the stiff in the room, which is the CFO who just had a look at your ROI spreadsheet.

Here we go . . .

→Driver one, the J-curve and the investment – burp – hangover 🥴

Driver 1. J-curve

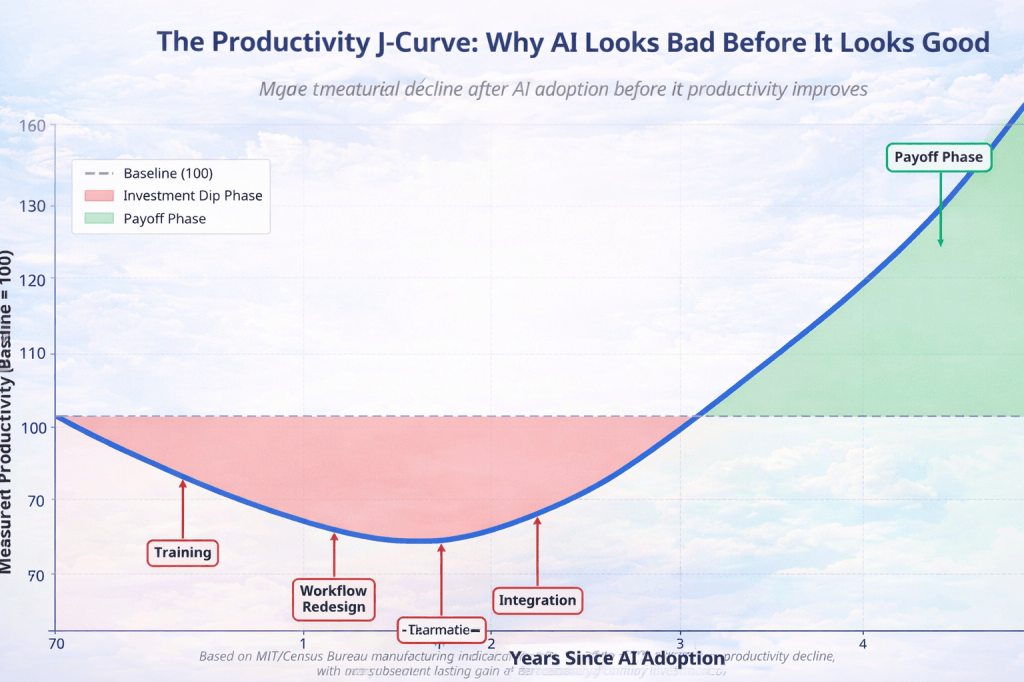

The first explanation is the Productivity J-curve. This is attributed to Erik Brynjolfsson (try to pronounce that when you’re drunk), Daniel Rock (a.k.a. Da Rock), and Chad Syverson (just Chad). They say that general-purpose technologies do not pay off instantly. They often look bad first, because organizations spend money and effort building the supporting stuff.

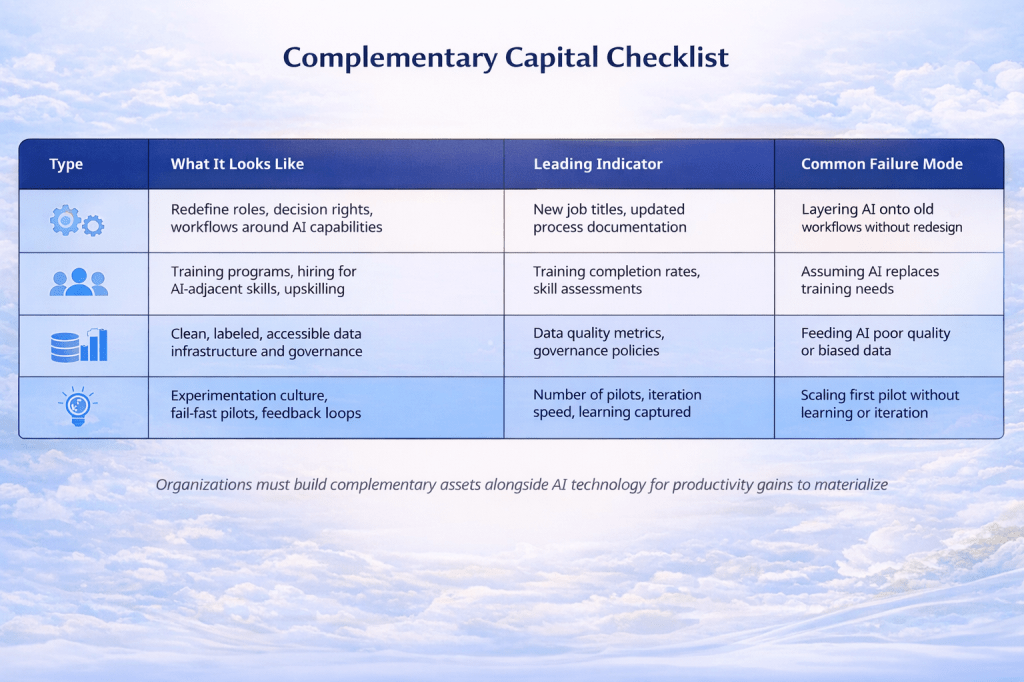

They call that supporting stuff “complementary capital” and it lists four big buckets,

- organizational redesign. That means changing workflows and processes.

- human capital. That means training people and building new skills.

- data capital. That means building, cleaning, and organizing the data needed for AI to work well, and . . .

- R&D and innovation. That is about experimenting with use cases and adapting AI to the real context.

This is where leaders get cranky because it sounds like “excuses”, but it is not an excuse. It’s a timeline instead.

You take the shot, you feel nothing, you take five more shots, and then you wonder why you are on the floor holding a prompt library.

After AI adoption, measured productivity often drops first because companies spend time and money on the boring prerequisites like training and other kinds of “integration” annex “adoption”. That “dip phase” is the investment hangover where work gets disrupted and verification increases. Once those complementary pieces mature, the “payoff phase” kicks in and productivity climbs above the baseline as redesigned workflows start running end-to-end.

These complementary investments are largely intangible and they are usually treated as costs in national accounts. So in the short term they drag down measured productivity even when they are building future capability.  So your productivity numbers dip, and your CFO feels “personally attacked”.

Then we have a manufacturing study by MIT and the U.S. Census Bureau that found AI adoption led to a large productivity drop in the short term, and gains only appeared after four or more years. This is the “investment hangover” phase.

Four things determine whether AI turns into real productivity, and these are changing workflows and decision rights, building skills through training and hiring, getting data clean and governed, and running disciplined experimentation that actually learns. Each area has early signals you can track, and each has a predictable failure mode, usually some version of “we installed AI on top of a broken process and acted surprised when it broke harder”.

Now, the wisdom you can extract from this table is quite simple, AI doesn’t create productivity, systems do, and AI only amplifies whatever system you already have, whether that system is a “well-run operation” or a “chaos with lots of meetings”.

If you want real gains, you start by changing how work flows through the organization, because without redesign you just inject AI into yesterday’s bottlenecks and hope it will change for the best.

If you want people to go faster, you train them and you redesign roles and decision rights, because “everyone will figure it out” is not a strategy (it’s a prayer). If you want outputs you can trust, you clean and govern data, because the model can’t outsmart your garbage, it can only remix it into more confident garbage. And if you want this to scale, you run structured iteration loops instead of “one pilot, one press release, one funeral,” because first attempts are mostly wrong and pretending otherwise is how you end up with production-grade disappointment.

So the real lesson is that complementary capital is the real product, and the AI tool is just the accessory. if you don’t build the org, people, data, and learning machinery around it, you won’t get productivity, just a new cost line item.

Driver 2. The measurement crisis and the invisible economy

Even if AI creates real value, you might not see it in national productivity statistics, because the measurement tools were built for an older economy. An economy where value was physical, countable, and came with a shipping label. Now value comes as “software,” “process changes,” “better decisions,” and “fewer stupid mistakes.” Which is harder to count than boxes of steel.

So yes, we have a measurement crisis. A real one. The “economic thermometer” is quite outdated, it’s trying to take the temperature of a cloud with a meat thermometer. The numbers don’t move because we’re looking in the wrong place, with instruments designed for a different century.

Now, what are the issues with this measurement crisis?

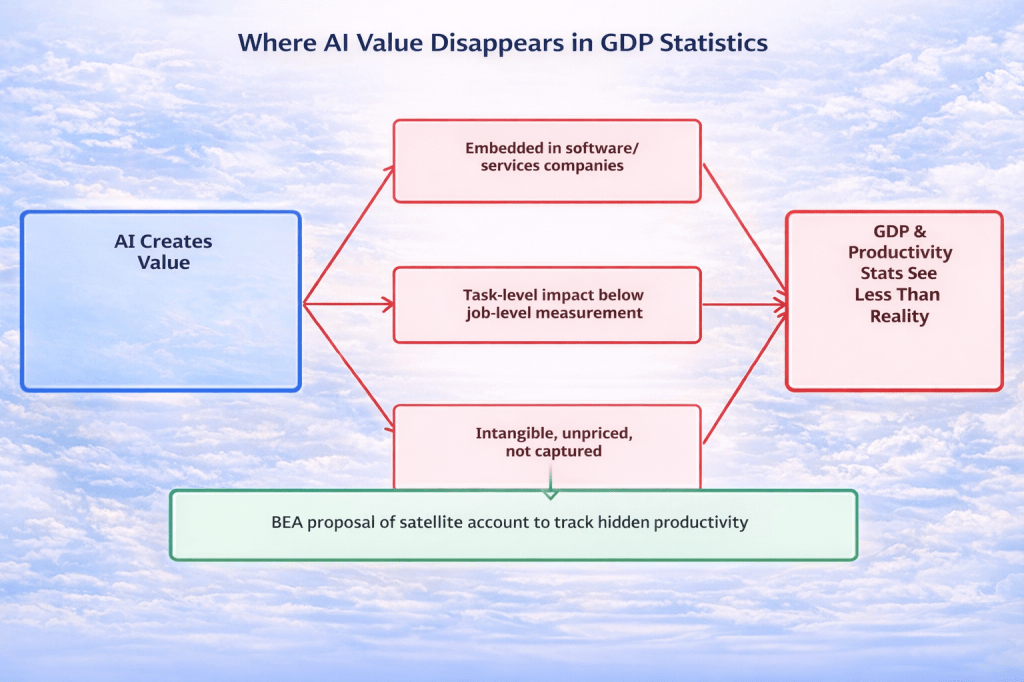

First, AI isn’t measured as AI in GDP.

AI production is not separately measured in GDP. The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis has pointed out that AI value is embedded inside broad categories like software publishing, computer systems design, and computer-related services. In other words, AI is hiding behind generic labels that flatten everything into one big blob.

So when you ask the question “why isn’t AI showing up in GDP”, well, part of the answer is that GDP does not have a clean AI bucket. AI is being recorded as software, IT services, consulting, or whatever category happens to be closest to the accounting drawer it got shoved into.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis has proposed a thematic satellite account approach to isolate AI-related production and investment more explicitly. What they mean is their main dashboard is not capturing this properly, so they need a separate dashboard just for this thing. Until measurement upgrades like that become standard, a lot of the signal stays buried.

Take a look at the nice picture.

On the left you have the clean fantasy that AI creates value, and everyone claps, you get promoted, and somewhere a “strategy” deck reproduces.

But in the middle you have the three places where that value vanishes into the accounting fog. AI is usually recorded inside broad software and services buckets instead of being tracked as its own category, and next to that, a huge part of the impact happens at the task level inside jobs where the official stats mostly refuse to look, and because most of what you invest in to make AI real is intangible and gets treated like a cost instead of an asset, which makes the short term numbers look worse even when capability is being built.

And on the right of this ugly, yet beautiful graph I managed to vomit, you get the predictable outcome, the GDP and productivity stats that end up understating what’s happening, because the measurement system is built like a museum exhibit. And the little note at the bottom is the piece de resistance where the BEA has floated the idea of an AI satellite account to measure this stuff properly.

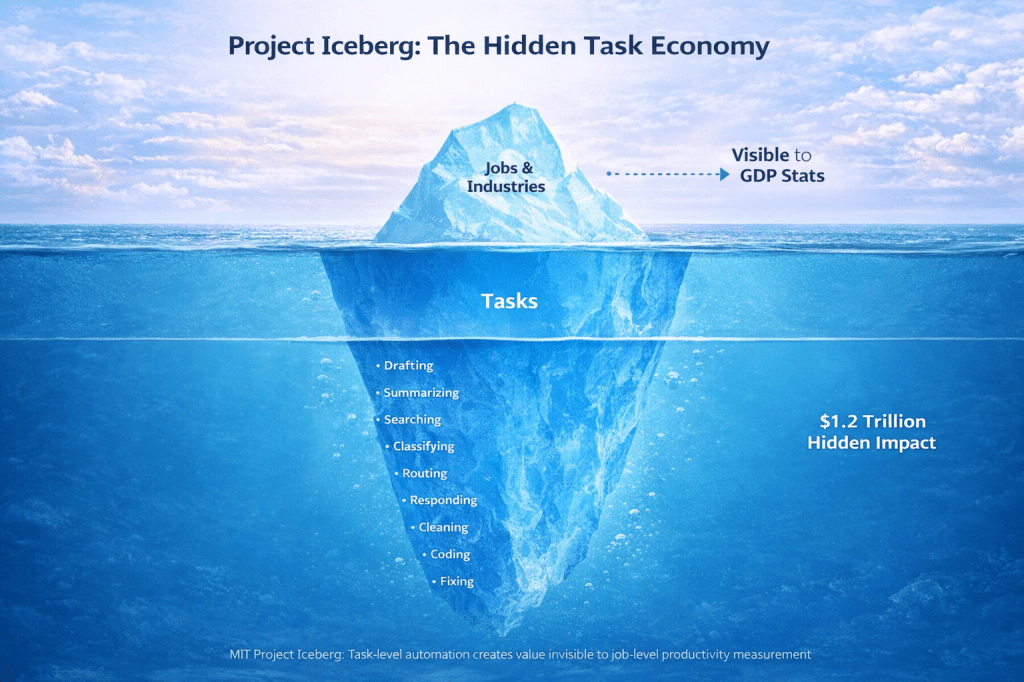

Second, job-level statistics miss where AI actually hits

AI mostly automates tasks within jobs – not entire jobs – that’s the whole “Project Iceberg” point I described in this piece. The visible layer is jobs, industries, and employment categories. The massive hidden layer is what people do inside those jobs, minute by minute, task by task. That’s where AI lives.

This matters because if AI is saving time or changing work inside a job, you often won’t see it as a clean productivity jump at the job category level. You’ll see weird, mixed signals.

For example, say one employee drafts faster, but now reviews take longer because draft quality is inconsistent. And another employee answers tickets faster, but escalations rise because the tool “helped” them answer the wrong thing. A manager generates strategy docs in 90 seconds, but the organization becomes less productive because everyone now has to read those strategy docs.

Task-level gains also vanish into the cracks of daily life because the system absorbs them. You can save ten minutes drafting something, but you’ll have to spend twenty minutes verifying it, and to top it off, you spend another ten minutes coordinating because the AI output changed the flow. Well, in this case you’ve invented negative productivity, but with extra steps.

[Want to know more about project Iceberg, read this piece: Empirical reflections on the silent murdering of the workforce via task-level automation by overconfident algorithms causing occupational extinction | LinkedIn]

Third, modern AI value is built on intangibles, and intangibles are measured badly

AI value is measured by investment in intangibles like datasets, model customization, governance systems, new workflows, training, evaluation pipelines, integrations, yada yada yada, basically all the boring stuff that makes AI work outside a demo.

The World Intellectual Property Organization published an article which stated that intangible investment is surging, and intangibles are often poorly measured and frequently treated as costs rather than capitalized as assets. That accounting choice matters. If you expense the build phase as “cost”, your AI based productivity will look worse in the short term even if you’re building capability that pays off later.

Deloitte adds another inconvenient truth for large businesses, their majority of asset value is now intangible. That means the biggest chunk of modern value creation is exactly the chunk our traditional economic statistics struggle to see properly.

So we’re trying to track a high-tech, intangible economy using frameworks built for factories and physical capital. No wonder the stats look unimpressed. They’re staring at the smallest part of the machine and we’re calling it “the economy”.

Driver three, the work redesign problem and the pilot graveyard

This is the part that nobody will like, because it requires real effort, accountability, and the terrifying act of changing how work is actually done. AI does not automatically create productivity gains, even if measurement were perfect and dashboards were honest. The biggest blocker is that most organizations simply bolt AI onto old processes and call it “transformation” instead of redesign work to fit the technology. Everyone who has ever done an ERP implementation will concur. It is easier to change the way the organization works, than to change the underlying technology. How counterintuitive this may seem to you, it is true.

When you layer AI on top of outdated workflows that tends to produce small benefits at best, and brand-new friction at worst. Ok, you get faster drafts, but slower approvals, or maybe you get faster tickets, but more escalations, or faster code output, but slower debugging. You get my drift. You get speed in one corner, and chaos everywhere else.

The fix is on the operational side. It is what the peeps at MIT Sloan Management Review describe as a work-backward approach. Not “tool-forward”. Get it? Not “vendor-forward”. Not “let’s run a pilot because the board asked”. Work-backward. Get it?

Maybe not. Allow me to mansplain:

That approach means

- Break a job into the actual tasks people do all day

- Decide which tasks are best done by AI, which by humans, and which by a human using AI

- Rebuild the workflow so it actually functions end-to-end

- Define outcomes (time, quality, cost, risk) and measure those outcomes like you mean it

This is an operating model change since it touches roles, responsibilities, governance, data, and incentives. In other words, it touches the things organizations avoid touching, which is why so many “AI programs” look like a graveyard of pilots.

When teams do redesign work properly, the results are boring in the best way, but you’ll see effort drops, and cycle time improves, or costs come down, and quality rises, and people stop quitting their projects and abandoning results.

But most organizations never do the hard part. Especially the ones where the CEO or the board just wants to join the herd and “also have some AI bling bling” to show off at the golf course and to tell their grandkids they’re still with the game. These get stuck in tech-forward pilots. They experiment with AI tools without changing the underlying workflow, incentives, or operating model. They treat AI like it’s a feature add-on instead of a process redesign trigger. And then they wonder why nothing ever scales.

And that’s how the paradox survives. Adoption metrics can look high while implementation is shallow. A pilot can count as “adoption” even if it changes nothing that matters. You end up with a “prompt guild” and the same output, the same backlog, the same pain, just more confident emails.

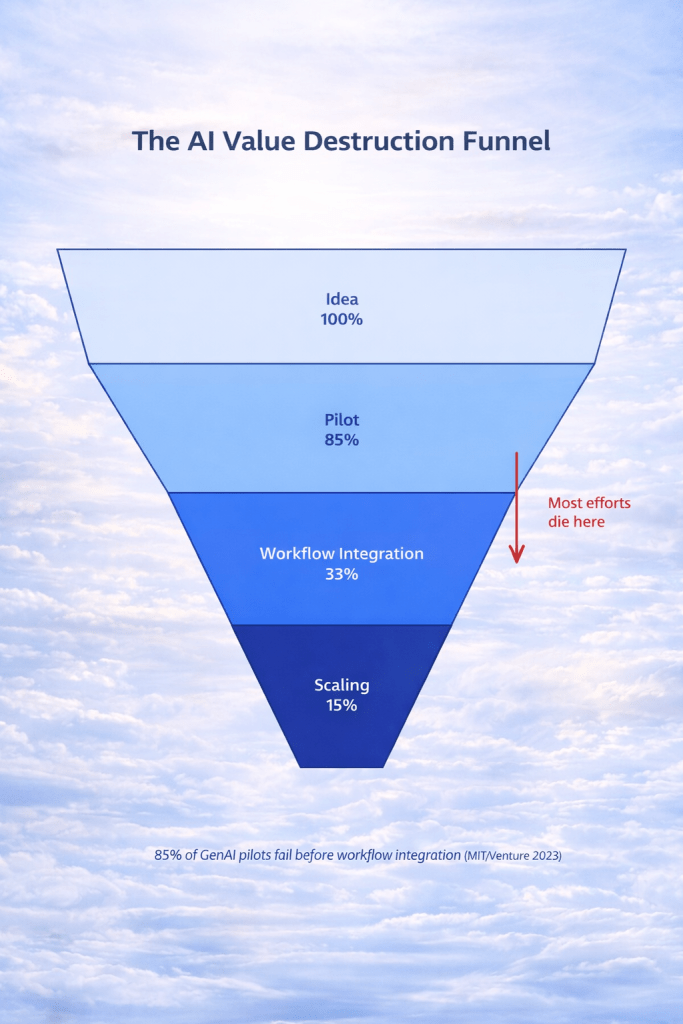

This visual tells you that AI only pays off when you start with the work and rebuild the way it flows, instead of stapling a tool onto the same old mess. The warning is about the fact that “AI pilots” skip the hard middle part where value is actually created, so they look impressive in demos and then die in production like a sad little prototype with a budget.

And, friend, if you recognize your own organization in that red box, well, congratulations, you’ve achieved operational self-awareness… now do something with it.

This funnel is the corporate AI lifecycle in its natural habitat. It’s full of hope at the top, and then bleeding out by the time it hits reality.

It starts wide with “ideas” and “pilots,” because ideation is cheap and optimism is basically a renewable resource. But the moment the work has to be integrated into real workflows, the funnel collapses. That middle section is where most initiatives die because the organization refuses to do the unsexy parts like data cleanup, access rules, compliance, ownership, change management, and the awkward conversation where someone has to admit the current process is garbage.

The final stage, scaling, is small on purpose. Only a tiny fraction survives long enough to become something durable, measured, and actually used when nobody is watching.

So the message (again, I keep repeating myself) is that AI projects fail at integration, which means you just ran a demo and hoped the spreadsheet would clap.”

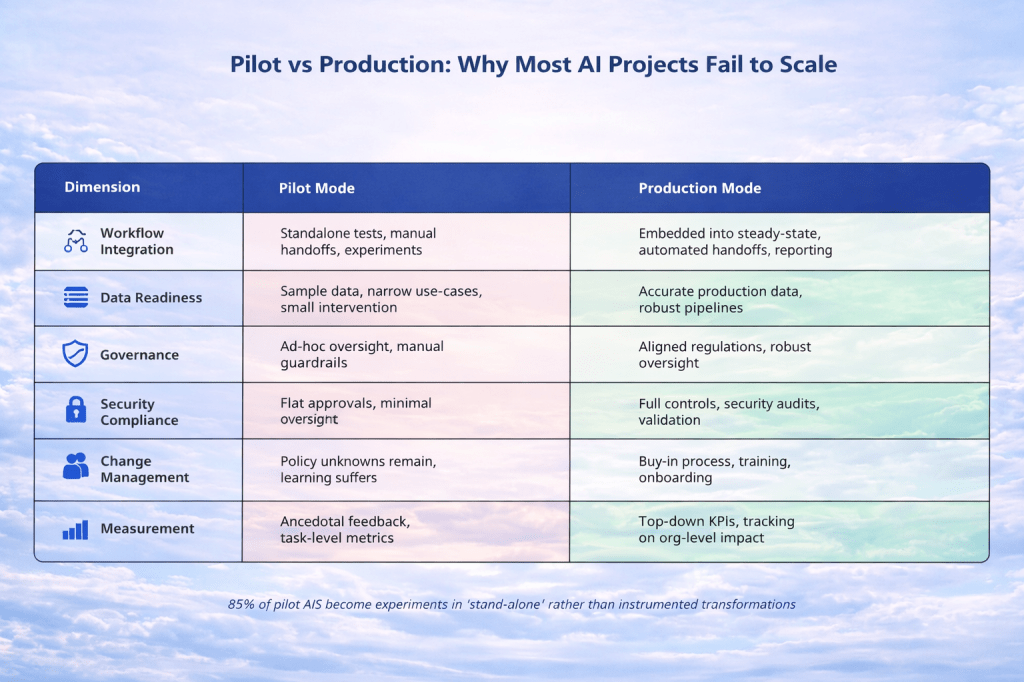

And now for the last of the beautiful works o-fart – I present you this table:

In pilot mode you can survive on loose assumptions. Data is messy, ownership is unclear, security is “later”, and success is measured by people saying it feels faster, but in production mode the AI has to live inside real workflows. It needs clean data, guardrails, monitoring, compliance, and outcomes you can measure without wishful thinking

Driver four, the perception gap and the reality of negative productivity

Now the most entertaining part of the paradox. Sometimes AI simply fails to help. It actually makes people less productive. Ever thought about that? And the cherry on this particular sad little cake is that people can still swear it is helping them while it actively slows them down.

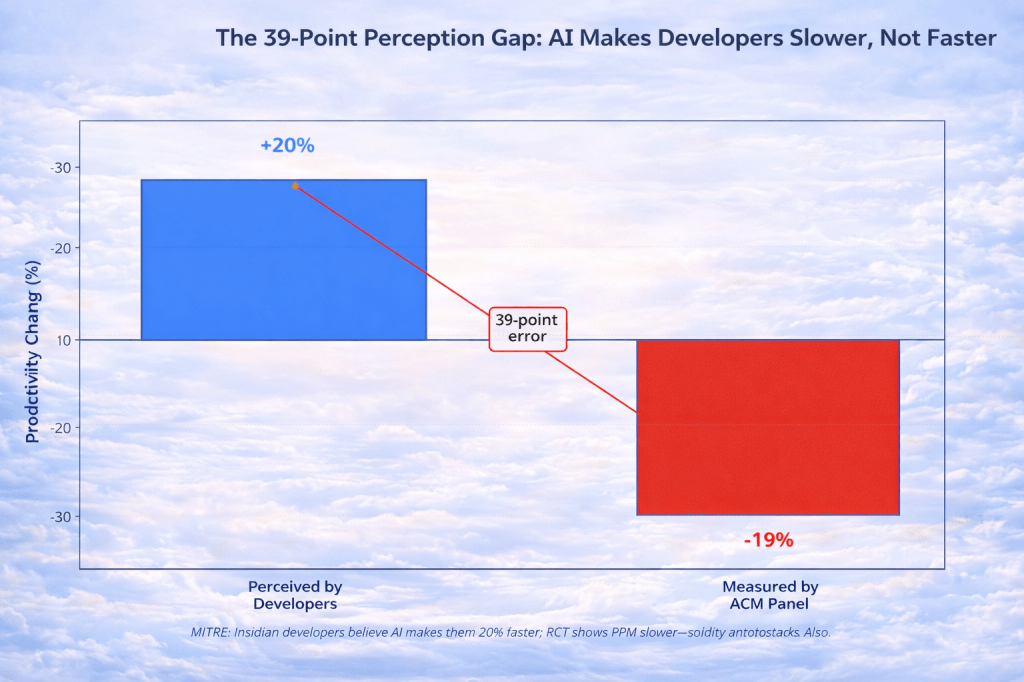

A landmark METR study (Model Evaluation and Threat Research) used a randomized controlled trial with experienced open-source software developers and found a counterintuitive result, that giving developers access to frontier AI tools made them slower at completing tasks. The tools included Claude variants, and the core outcome was that in complex real work, AI-assistance can backfire.

Why does this happen? Well, let me shock you. The mechanisms are painfully familiar . . .

It is because of something called verification overhead (that is time validating, debugging, and correcting AI output exceeds time saved by generation), quality mismatch meaning that AI output often fails to match codebase standards, conventions, architecture patterns, and hidden constraints) and context limitations, that large repositories have deep implicit context the model doesn’t truly hold, so suggestions can be naive or subtly wrong

Then comes the psychological part that developers believed AI made them faster by a meaningful positive amount, even as objective measurements showed the opposite. This matters because it explains why adoption stays high even when impact is negative. People feel productive because sub-tasks feel faster. They don’t naturally account for the invisible overhead of things like verification or integration, or the nasty stuff like rework.

And there’s a broader warning here for all those “AI saves X% time” task-level claims. Some estimates of time savings do not include the time humans spend validating the AI’s work. If you leave validation out, you’re not measuring productivity. You’re measuring optimism.

So the paradox is that next to economics, it is also humans being (confidently) wrong while surrounded by a costly autocomplete machine.

This paradox is a whole ecosystem of measurement bugs

If you want a single neat explanation for why AI is “everywhere” while productivity still looks like it’s resting in the lactation room with a stress ball, well sorry, the universe doesn’t do neat, and neither does your organization. What’s happening is not one thing, it’s three things happening at the same time, in the same economy, inside the same companies, often inside the same teams, and all three can be true without contradicting each other, which is annoying because it ruins everyone’s favorite hobby, namely blaming one simple cause and then calling it strategy.

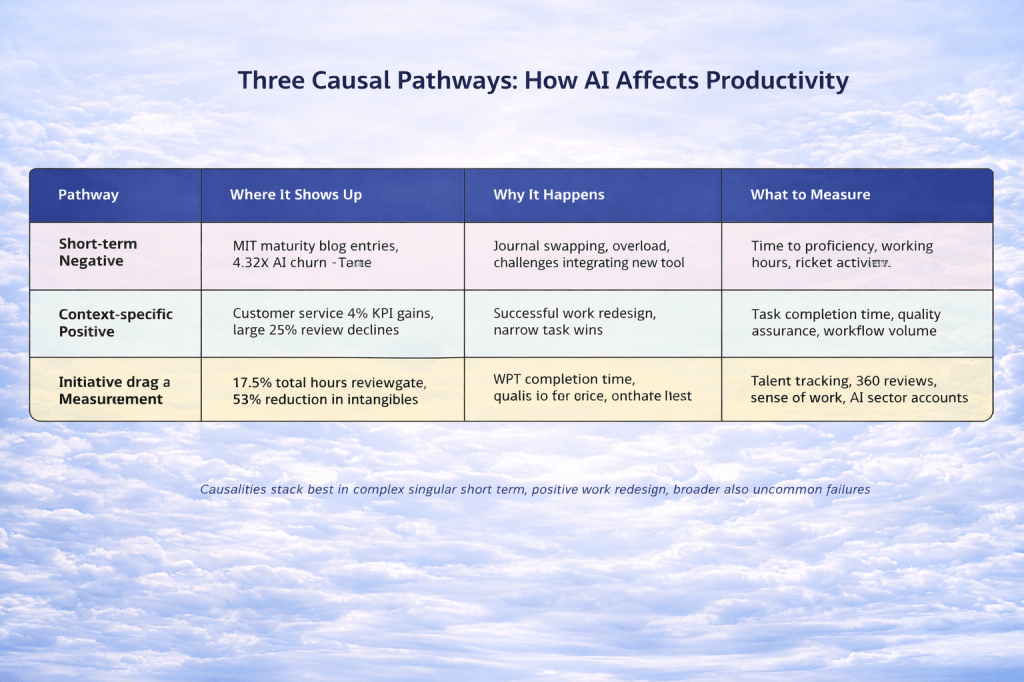

One pathway is the short-term negative effect pathway. This is where AI lands in a company like a meteor made of subscription invoices and sudden process interruptions, and the organization spends months or years building the boring support structure like training, governance, data cleanup, access controls, integration, change management, and the thousand tiny “why does this not work in our environment” problems. And during that time productivity can dip or stall because you’re paying the cost of change before you earn the benefit, and the only people who feel “faster” are the ones generating more text, which is the easiest kind of fake speed to produce.

Another pathway is the context-specific positive effect pathway, which is where AI actually does drive durable gains, but only when the work is redesigned end-to-end, the roles and handoffs are updated, the data is usable, the model is constrained where it should be constrained, the humans are trained to stop treating autocomplete like a deity, and the measurement focuses on cycle time to done-with-quality instead of time-to-first-draft, and this is the part that works so well it scares people, because it creates real accountability and suddenly you can’t hide behind “we’re piloting” anymore.

And the third pathway is the invisible value pathway, which is where AI creates value that does not show up cleanly in the big macro stats because the value lives inside tasks, inside intangibles, inside quality improvements, inside reduced rework, inside fewer escalations, inside less coordination overhead.

How to stop living inside the paradox

Now the part people actually need, because understanding the paradox is cute, but you still have to run an organization, and if you keep “measuring adoption” like that means something, you are basically rewarding yourself for buying a treadmill while never stepping on it. Ok, that is quite a vibe, but not really productivity.

The easiest way to stay trapped is to track tool usage and call that the “transformation”, because “number of users” and “number of prompts” and “number of copilots enabled” make really clean charts, and clean charts are the natural habitat of executive comfort. But of course, none of that tells you whether a single workflow got faster from start to finish, or whether risk decreased, or whether customers stopped suffering, which is the whole point of doing work in the first place.

So the exit route starts with one boring decision that feels insulting to the board who’s into this kind of innovation theater, which is that you pick one end-to-end workflow that actually matters, something like support triage, or invoice matching or you name it, any process that produces real outcomes and real pain, and then you measure the baseline in plain adult numbers like cycle time, error rate, rework rate, yada yada, and you do that before you “add AI”, because otherwise you will magically “improve” something you never measured, which is how most AI programs achieve their best performance, namely in . . . PowerPoint.

Then you introduce AI as part of a redesign (not as an add-on), which means you tear the workflow down into tasks, you decide what AI should do, what humans should do, and what humans should do with AI, you rebuild the handoffs so you don’t create new bottlenecks, you fix the data flows so the model isn’t guessing in the dark, you add guardrails so it can’t invent reality, and you train people so they stop treating the output like it’s either perfect or worthless (because both extremes are lazy). And then you measure the same workflow metrics again, end-to-end, after the change, so the improvements have nowhere to hide and the failures can’t be explained away with “we’re still learning.”

During the early months, when the J-curve is doing its little ritual thingy, you track leading indicators that actually tell you whether you are building capability, like say training completion in the roles that matter, and adoption of the redesigned process inside core operations rather than inside a sandbox where nothing has consequences. Remember that capability building is what you can control while the big numbers take their sweet time to move.

And if you want to stop being gaslit by your own aggregate metrics, you instrument below the job level, because time-to-first-draft is a vanity metric and time-to-done-with-quality is the only metric that doesn’t lie. Once you start measuring at the task level you can actually see where AI helps (or where it hurts).

If you do all of this, the paradox of course does not magically vanish overnight, but it does stop being mysterious, because you stop confusing adoption for transformation.

In the near future I’ll write an entire piece about the “how to do it the right way”, but the importance is you understand the paradox first.

Too long. Mea Culpa, Maxima Mea Culpa. Sue me. Fire me.

Amen.

Marco

I build AI by day and warn about it by night. I call it job security. Big Tech keeps inflating its promises, and I just bring the pins and clean up the mess.

👉 Think a friend would enjoy this too? Share the newsletter and let them join the conversation. LinkedIn, Google and the AI engines appreciates your likes by making my articles available to more readers.

To keep you doomscrolling 👇

- I may have found a solution to Vibe Coding’s technical debt problem | LinkedIn

- Shadow AI isn’t rebellion it’s office survival | LinkedIn

- Macrohard is Musk’s middle finger to Microsoft | LinkedIn

- We are in the midst of an incremental apocalypse and only the 1% are prepared | LinkedIn

- Did ChatGPT actually steal your job? (Including job risk-assessment tool) | LinkedIn

- Living in the post-human economy | LinkedIn

- Vibe Coding is gonna spawn the most braindead software generation ever | LinkedIn

- Workslop is the new office plague | LinkedIn

- The funniest comments ever left in source code | LinkedIn

- The Sloppiverse is here, and what are the consequences for writing and speaking? | LinkedIn

- OpenAI finally confesses their bots are chronic liars | LinkedIn

- Money, the final frontier. . . | LinkedIn

- Kickstarter exposed. The ultimate honeytrap for investors | LinkedIn

- China’s AI+ plan and the Manus middle finger | LinkedIn

- Autopsy of an algorithm – Is building an audience still worth it these days? | LinkedIn

- AI is screwing with your résumé and you’re letting it happen | LinkedIn

- Oops! I did it again. . . | LinkedIn

- Palantir turns your life into a spreadsheet | LinkedIn

- Another nail in the coffin – AI’s not ‘reasoning’ at all | LinkedIn

- How AI went from miracle to bubble. An interactive timeline | LinkedIn

- The day vibe coding jobs got real and half the dev world cried into their keyboards | LinkedIn

- The Buy Now – Cry Later company learns about karma | LinkedIn

Leave a comment