I have been thinking a lot about the pushback I sometimes get when I talk positively about what AI can actually do. Which is funny, because optimism about AI seems perfectly fine as long as it stays vague, harmless, and doesn’t come with a bill attached.

That reaction surprised me at first. I’m not hyping anything. I’m just being honest. AI has been genuinely transformative for me, in very concrete ways. Real work. And with real results even.

Then it clicked.

Yeah, that sometimes happens.

The problem isn’t the technology. It is the receipt. The bill. The invoice.

People are comfortable with AI as an idea. When it is presented as a demo, or when it is incorporated in a toy – a physical gadget or when it’s a free tier curiosity. In that form, AI feels safe. Everyone can like it. Everyone can agree it is “interesting”. AI is still abstract at that stage. It lives in screenshots, keynotes, and marketing videos and it is something you observe, not something you rely on. There is no pressure to compare outcomes, no moment where you have to ask yourself whether someone else might be doing the same work faster, better, or cheaper because they’re using it differently. But the moment when their optimism is backed by experience, and worse, by the fact that is costs a lot, then you see something shifts. And suddenly you see their tone change. Their smiles tighten, and their questions get sharper. Their initial enthusiasm backs away toward “healthy skepticism” and “let’s wait and see”.

Not that the tech stopped working, but because the story stopped being free. If it works and it costs money, then access matters. And once access matters, people instinctively start asking uncomfortable questions like who gets it, and who doesn’t. And whether that difference actually shows up in results.

And that’s where the bigger issue starts to appear.

If AI actually works, and if it gets meaningfully better when you pay more for it, then access suddenly matters. A lot. What looked like a fun, shared future starts to look uneven. Some people get better tools while others get watered-down versions, but most get demos.

This isn’t a theoretical issue. We already know from decades of technology adoption that productivity gains don’t distribute evenly.

The people who benefit first are those who can afford early access, training, and experimentation. AI just compresses that dynamic into a much shorter time frame.

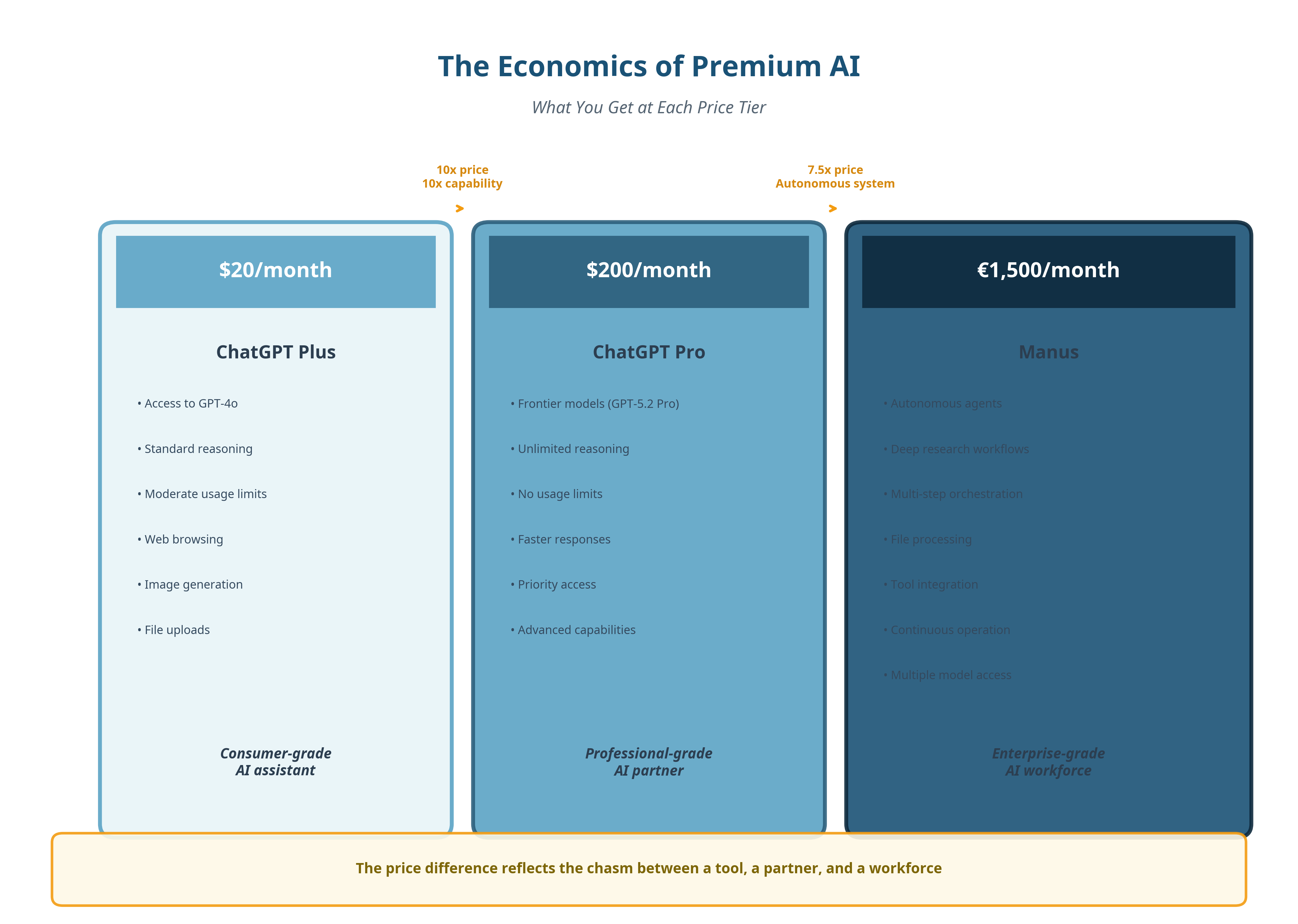

And yes, I am in the fortunate position that I’m able to try out different models and reserve a budget for them. I rationalize these investments to myself by saying that I need it for my work, and that is true to a certain extent, but it is mostly driven by curiosity and the willingness to just “play with tech”. For instance, I think paying 20 bucks for ChatGPT is too much (even though it’s a top tier model), yet I don’t mind spending 7000% more on Manus, which can use ChatGPT, Gemini and on top of that adds a lot of value.

That discrepancy only makes sense once you stop thinking in terms of “AI tools” and use AI in terms of output per unit of time. At the higher end, you’re not paying for answers but for sustained reasoning, orchestration, verification, and autonomy.

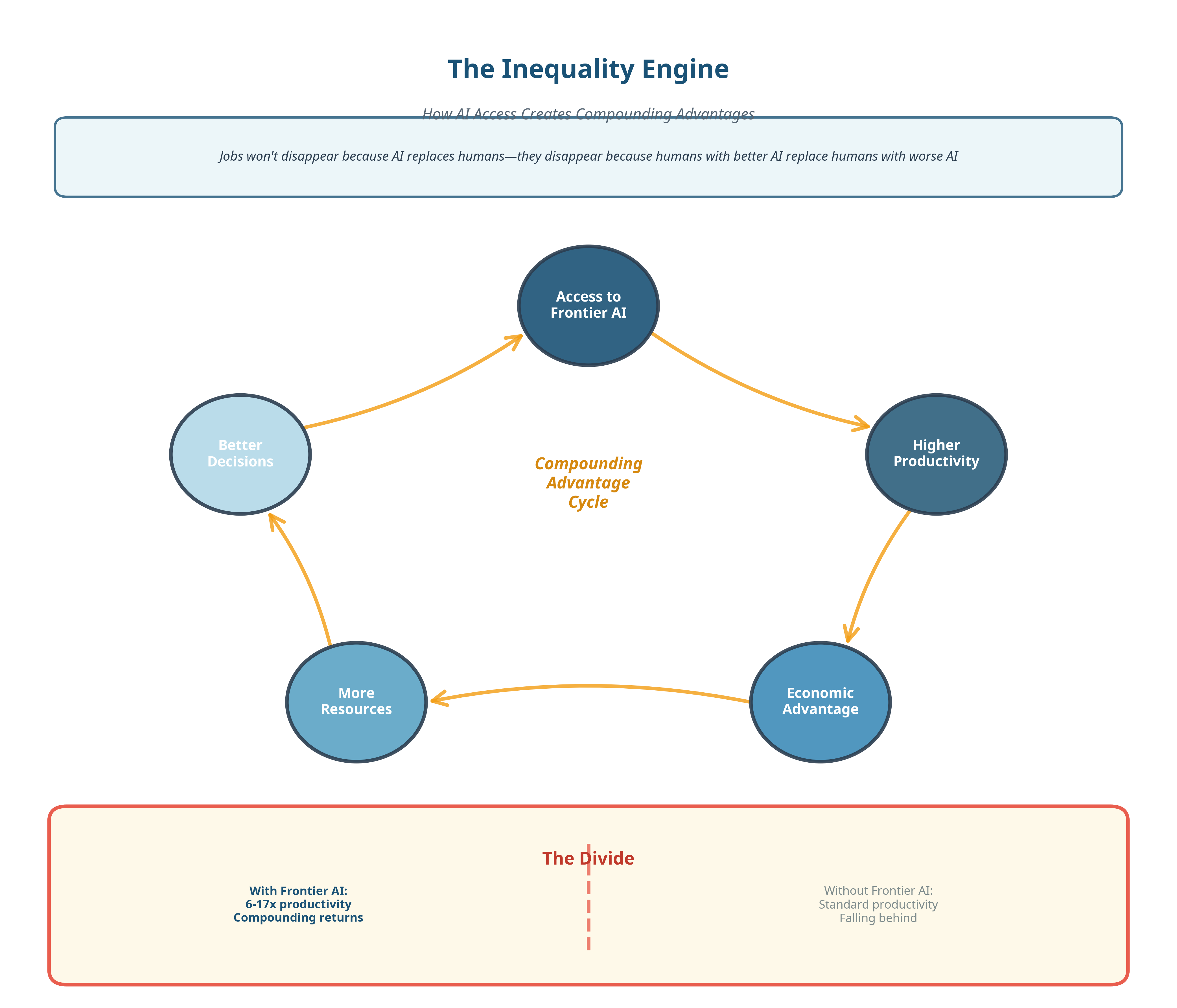

That’s why, paradoxically, today’s AI path is more likely to increase inequality than to “democratize intelligence”.

Not because intelligence can’t be shared, but the versions that really make a difference are becoming outrageously expensive. As in “nice future you’ve got there, shame if only hedge funds can afford it”.

This is where the word “inequality” earns its place, and I’m not using it as a moral statement, but as a structural outcome because when the cost of better reasoning scales faster than wages or general access, capability concentrates. And once capability concentrates, outcomes follow.

The thing is that the difference between how most people think about AI and how I experience it mostly comes down to spending. And no, I’m not saying people are cheap. But what I am saying is that good AI is expensive. Sometimes uncomfortably so.

And that’s exactly the problem I’m trying to convey.

Once you start paying attention to what changes when you spend more, the picture becomes clearer. The strongest AI systems are not just slightly better. They operate in a completely different league. But almost no one uses them, not because they don’t want to, but because they can’t justify the cost.

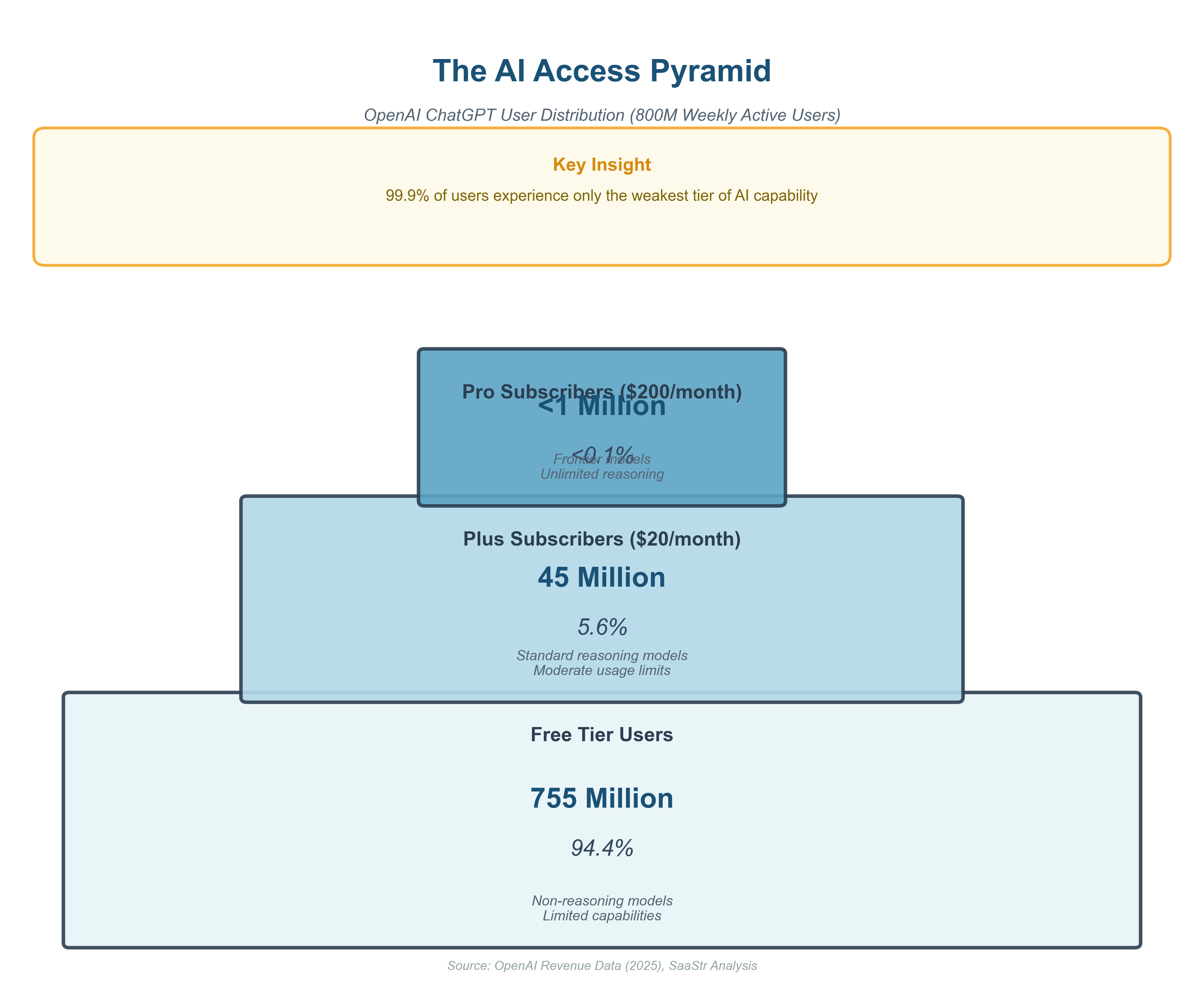

Usage data confirms this.

Hundreds of millions of people interact with AI weekly, but only a tiny fraction ever touch reasoning-heavy models. Cost-sensitive defaults dominate even among developers. The problem is that the public image of AI is shaped almost entirely by the weakest tier of capability.

So in this article, I set out to make this concrete.

I’ll explain what actually separates frontier AI systems from the models most people interact with, show the data that makes it clear how rare real access is, unpack why these systems are so expensive to run in the first place, and then look at what governments could do before this path hardens into a permanent divide.

This builds on ideas I’ve explored earlier, where I tried to explain AI from first principles for people who don’t need hype, but do want to understand what’s really going on.

More rants after the messages:

- Connect with me on Linkedin 🙏

- Subscribe to TechTonic Shifts to get your daily dose of tech 📰

- Please comment, like or clap the article. Whatever you fancy.

Some AIs think and others only talk

When most people think about AI today, they usually think of one thing: chatbots. Tools like ChatGPT or Gemini come to mind immediately. You type a question, you get a text answer, and that feels like the whole story.

What almost no one realizes is that there are very different kinds of AI behind those answers. And the difference between them is not cosmetic. It fundamentally changes what the system can do, how reliable it is, and who actually benefits from using it.

Broadly speaking, most people encounter two types of AI models, even if they don’t know those categories exist.

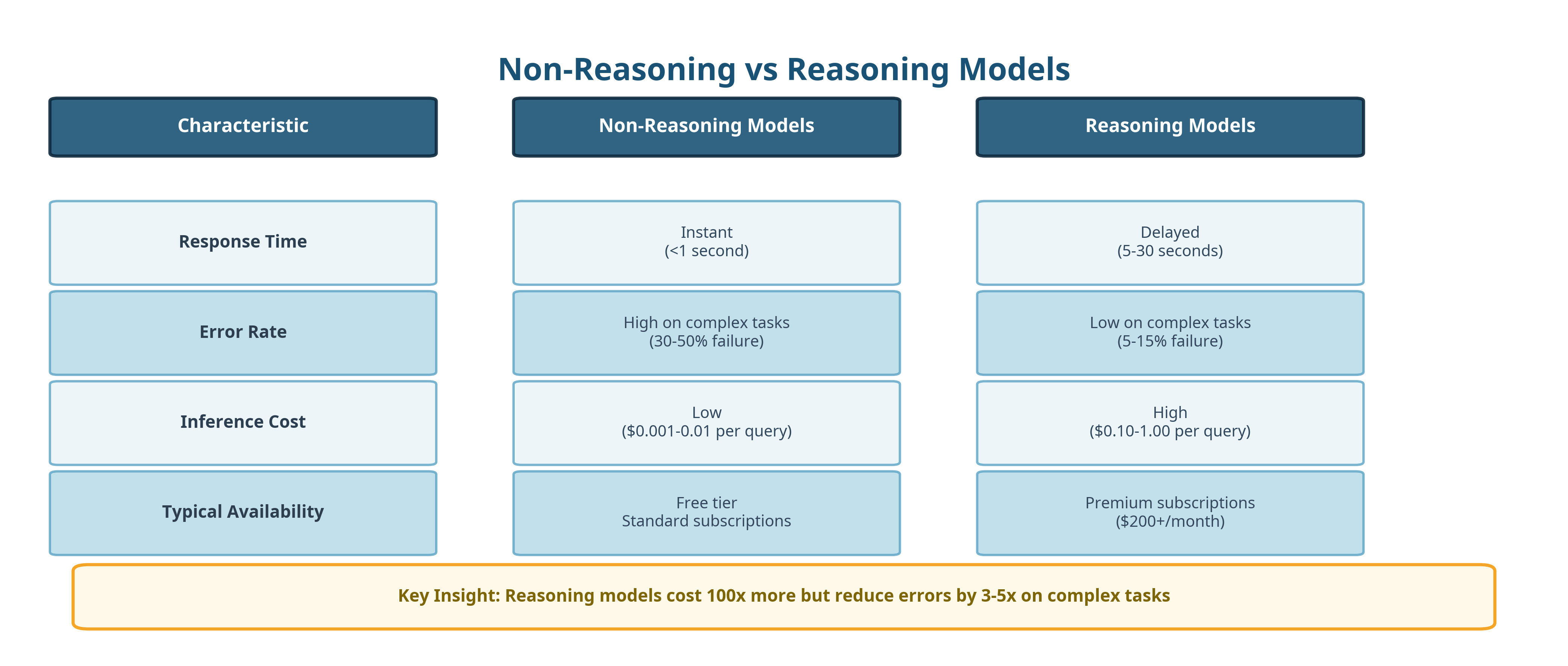

The first type responds immediately. You ask a question and it gives an answer right away. These are often called non-reasoning language models. They are optimized for speed and cost. They are very good at producing fluent text, summarizing information, and sounding confident.

What they do not really do is think.

Technically, these models predict the most likely next words based on patterns in data. They do not stop to evaluate whether an answer makes sense. They do not verify intermediate steps or explore alternatives and when something sounds statistically plausible, they will say it. That is why they can feel impressive at first and disappointing the moment you rely on them for anything that requires precision.

The second type behaves very differently.

These are commonly referred to as reasoning models. These do not respond instantly, they pause, and then break a problem down into steps. They explore multiple solution paths at the same time and check their own work before replying.

That extra effort leads to much better results, especially for tasks where correctness matters like mathematics, programming, planning, analysis, research, or complex decision-making.

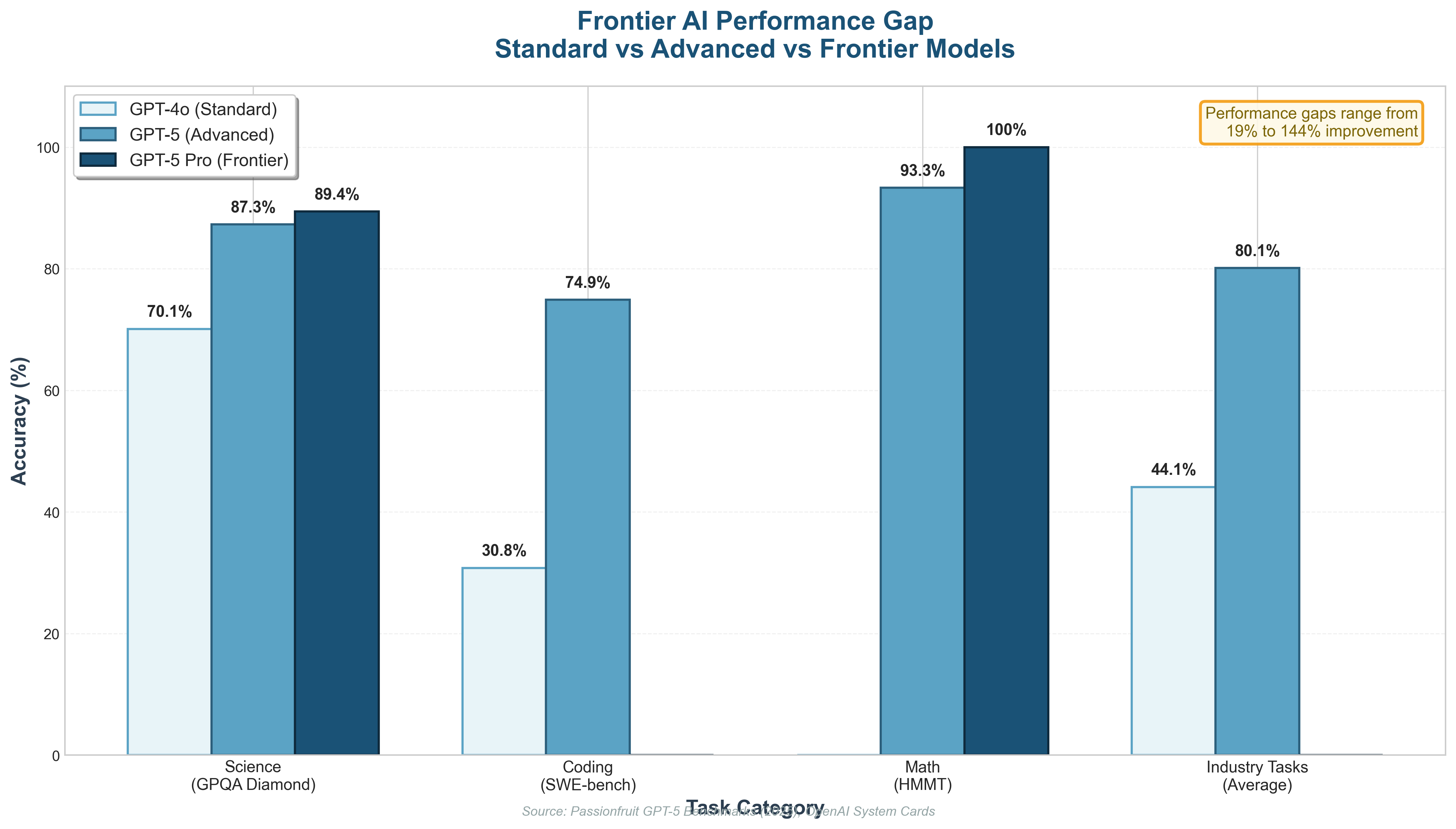

This difference is not small. Benchmarks consistently show that reasoning models make far fewer logical errors and solve a much higher percentage of complex tasks correctly. And here is the part that matters more than most people realize.

Quite literally, thinking costs money.

Reasoning models use far more computing power when answering a question. That extra computation is called inference-time compute. In plain language, it means the model is allowed to spend more time and more electricity thinking before it speaks.

This is where things change, and the magic turns into a price list.

Most people are not aware that this distinction exists. They judge “AI” based on the cheapest tier they have access to. When answers feel shallow, they conclude that AI itself is shallow. When mistakes happen, they conclude that AI is unreliable. What they don’t see is that they are evaluating the technology based on its weakest version. That gap remains invisible to most people because they are still standing on the free side of it. And that is also where the real consequences begin, slowly and quietly, without a launch event or a press release.

That said, even this distinction between reasoning and non-reasoning models does not fully explain how AI actually operates in everyday life.

AI you choose vs AI you don’t notice

You are already surrounded by AI, and you have been for years. The key difference is not whether AI is present, but whether you are consciously interacting with it. The AI you notice is the AI you actively choose to use. Chatbots. Writing tools. Image generators. These tools feel new because they are interactive. You type something and get a response addressed directly to you. But the AI you don’t notice is far more widespread and far more influential, it decides which results appear at the top of Google Search or which videos show up on YouTube and TikTok. It shapes Netflix recommendations, and Meta’s advertising systems that decide which posts appear in your feed and which ones never reach you at all.

This kind of AI has been shaping the internet for well over two decades. Long before ChatGPT, AI systems were already filtering information, ranking content, and targeting attention at massive scale.

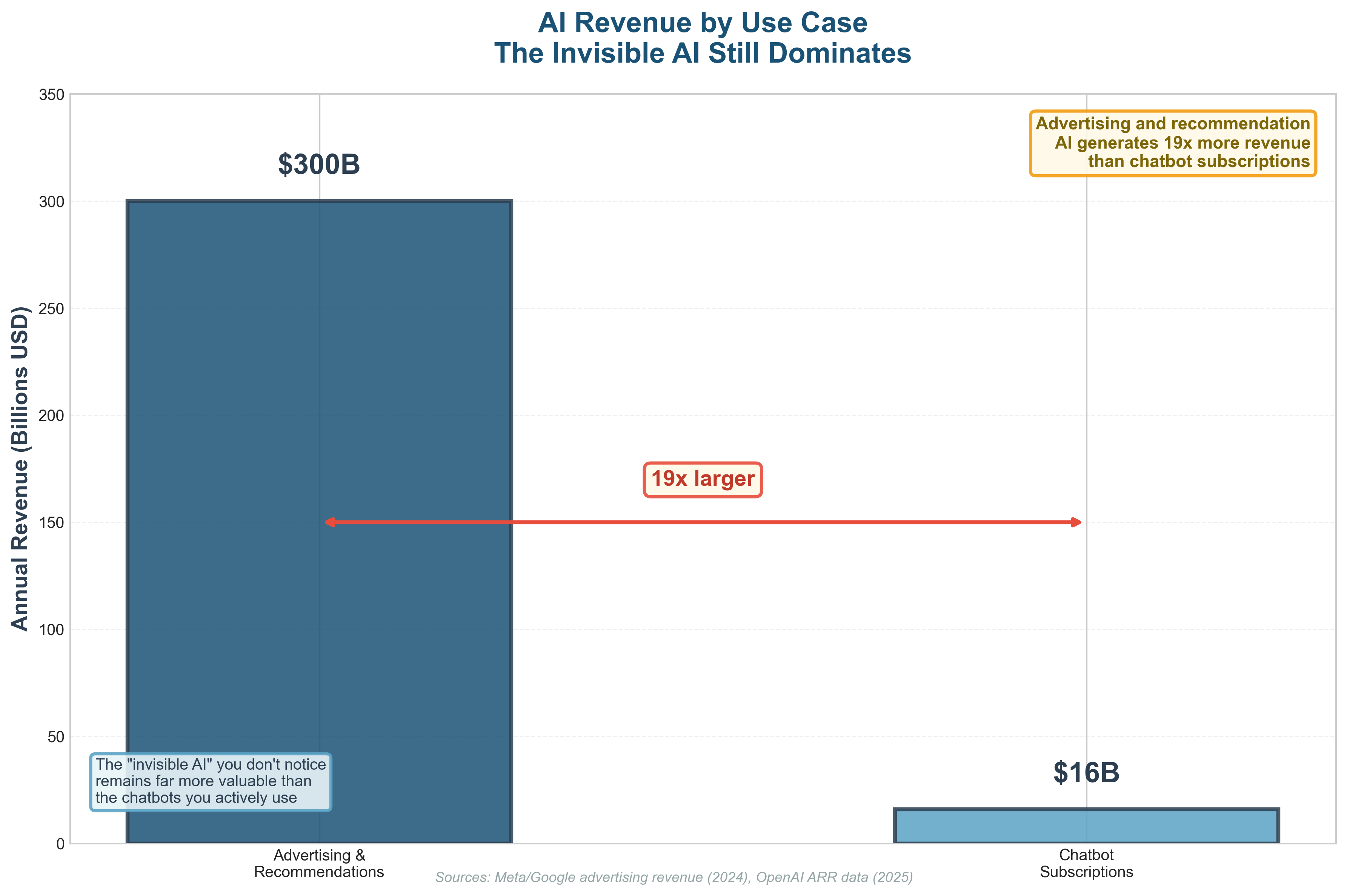

This is still the most valuable application of AI today (from a business perspective). Advertising and content targeting generate hundreds of billions of dollars annually. Chatbots, by comparison, are still small.

The reason chatbots attract so much attention is simple. They are the first AI systems most people interact with directly. You ask a question and receive a response that feels personal. Almost intimate. As if the machine is finally listening, instead of quietly profiling you for ad placement.

Better AI simply uses more computing power

This brings me back to the distinction between non-reasoning and reasoning models. The AI models that are driving investment today, and the ones requiring massive new data centers, they fall into two camps. Non-reasoning models respond immediately, confidently, and often incorrectly. And then there are the reasoning models that pause, reflect, and then respond. Which turns out to be extremely useful when the task involves thinking.

The mechanism behind this is inference-time compute which allows the model to spend more compute and generating an answer dramatically improves accuracy and reliability. It basically boils down to burning more electricity so the answer sucks less.

Reasoning models outperform non-reasoning models on almost every meaningful task like math, or coding and even planning a complex trip requires some thinking, and the same goes for analyzing documents and producing coherent PowerPoint presentations. Anything that benefits from careful reasoning benefits from models that are allowed to think longer.

This performance gap is so large that the entire AI hardware industry now assumes reasoning models will dominate the future (of LLMs). The focus has shifted away from making single chips faster and toward scaling systems, increasing memory bandwidth, and optimizing inference-heavy workloads.

The short version remains the same.

Thinking costs money.

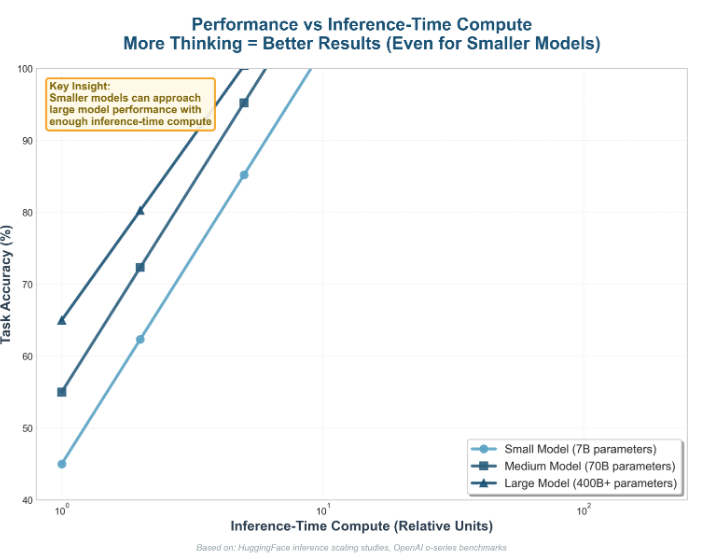

Data from open benchmarks shows that even relatively small models can approach the performance of much larger ones if they are allowed to run longer or try multiple solution paths. Intelligence, in practice, can be brute-forced with enough compute.

But that compute is metered (and billed).

Modern systems encourage models to reason step by step, and that reduces mistakes and hallucinations and occasionally produces something that resembles competence. That is exactly the reason why ChatGPT 5.2 now only has a 10% chance of producing errors. That is roughly 11 responses out of a 100 that contain mistakes or incorrect facts, and with web browsing enabled the hallucinations drop below 6%, where the model accesses verified search results. And when you are using RAG to complement your model, hallucination rates drop below 1%. And a large portion of this success is because of longer reasoning.

The takeaway is that more inference-time compute equals smarter behavior, regardless of model size. If you are unsure which model you need, imagine a human answering your question. If you would give them a few minutes to think, you want a reasoning model.

The reality behind AI adoption rates

The problem is that almost no one is actually using reasoning models.

Most people judge AI based on weaker models because the better ones live behind paywalls that range from expensive to insulting. Serving reasoning models costs a fortune so AI labs hide them behind subscriptions that most users will never touch.

The data makes this painfully clear.

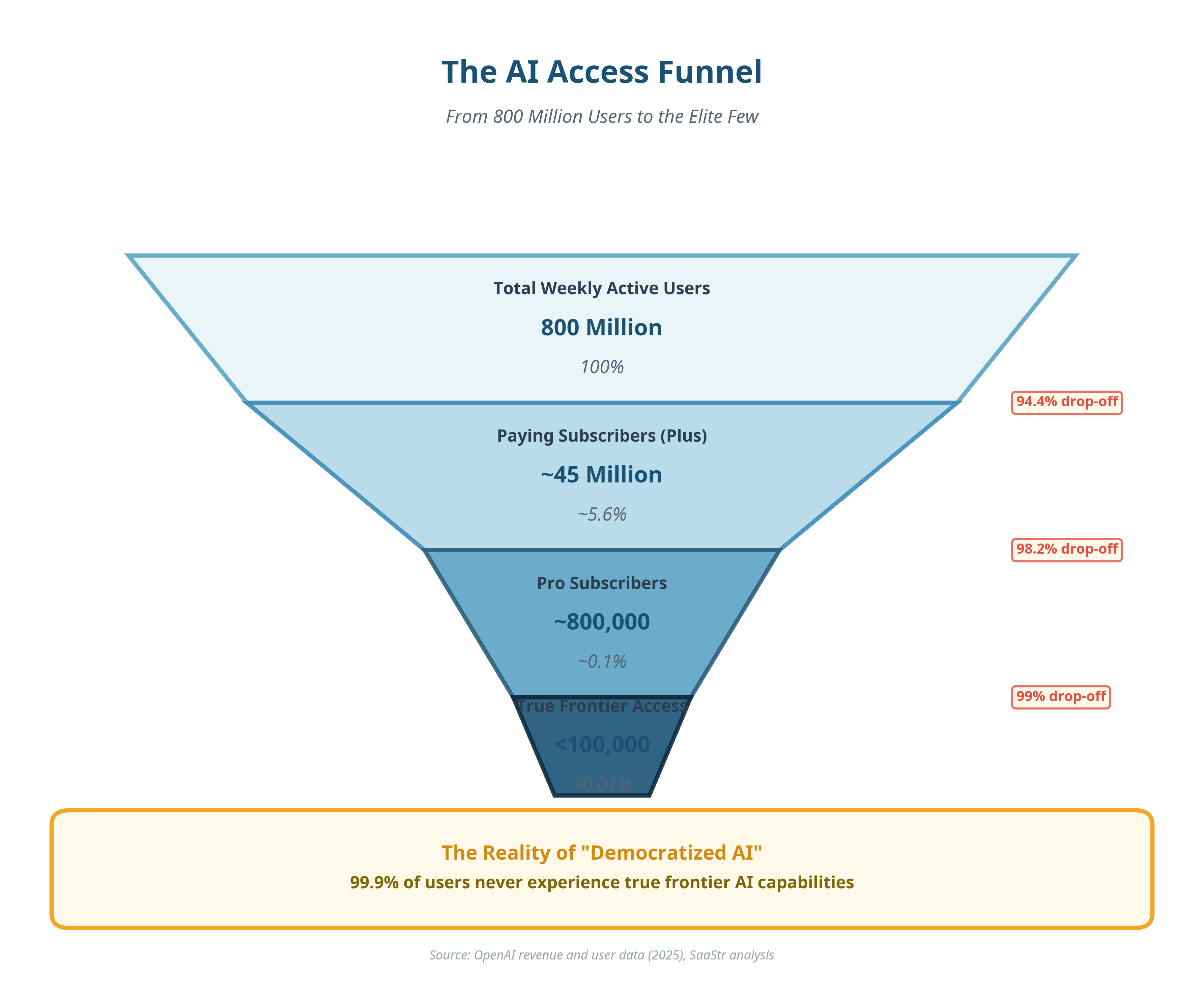

OpenAI has around 800 million weekly active users. On paper, that sounds like a money printer but in reality, only about 5 percent of users pay for any subscription at all.

Even among paying users, only a tiny fraction pay $200 per month for ChatGPT Pro, which unlocks access to true frontier systems.

Free and Plus users may occasionally encounter reasoning models, but routing systems almost always send requests to the cheapest viable option. Because kindness does not pay the electricity bill.

The result is stark.

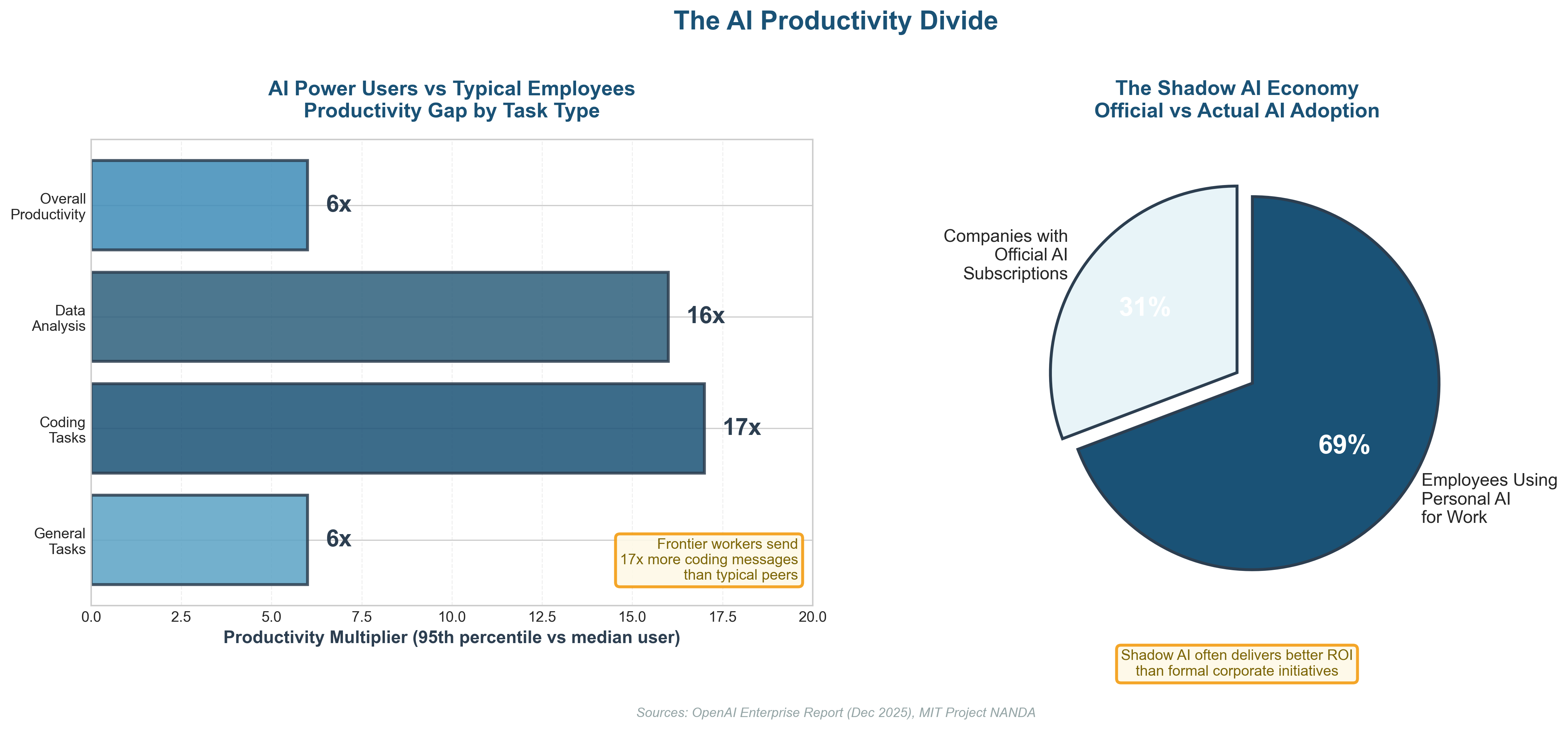

Fewer than 5 percent of users meaningfully interact with reasoning models. Fewer than 0.1 percent experience the real frontier. And API usage tells the same story. Cheap models dominate, even among developers.

The divide between casual users and the AI “elites”

Ok, ‘elites’ is a bit exaggerated, but you know what I mean, the people who can afford the extra cash to pay for models that produce better results – not only using the free tier. If 99.9 percent of people use mediocre models while 0.1 percent use frontier systems, that gap compounds very quickly.

Most people are interacting with something approximating Peter Griffin with autocomplete, and only a small minority interacts with something closer to a postdoc.

Yes, I know, comparing AI to humans is a bad analogy, but still, the difference between basic and frontier models is so extreme that it feels like talking to different species.

And this brings me to the second premise . . .

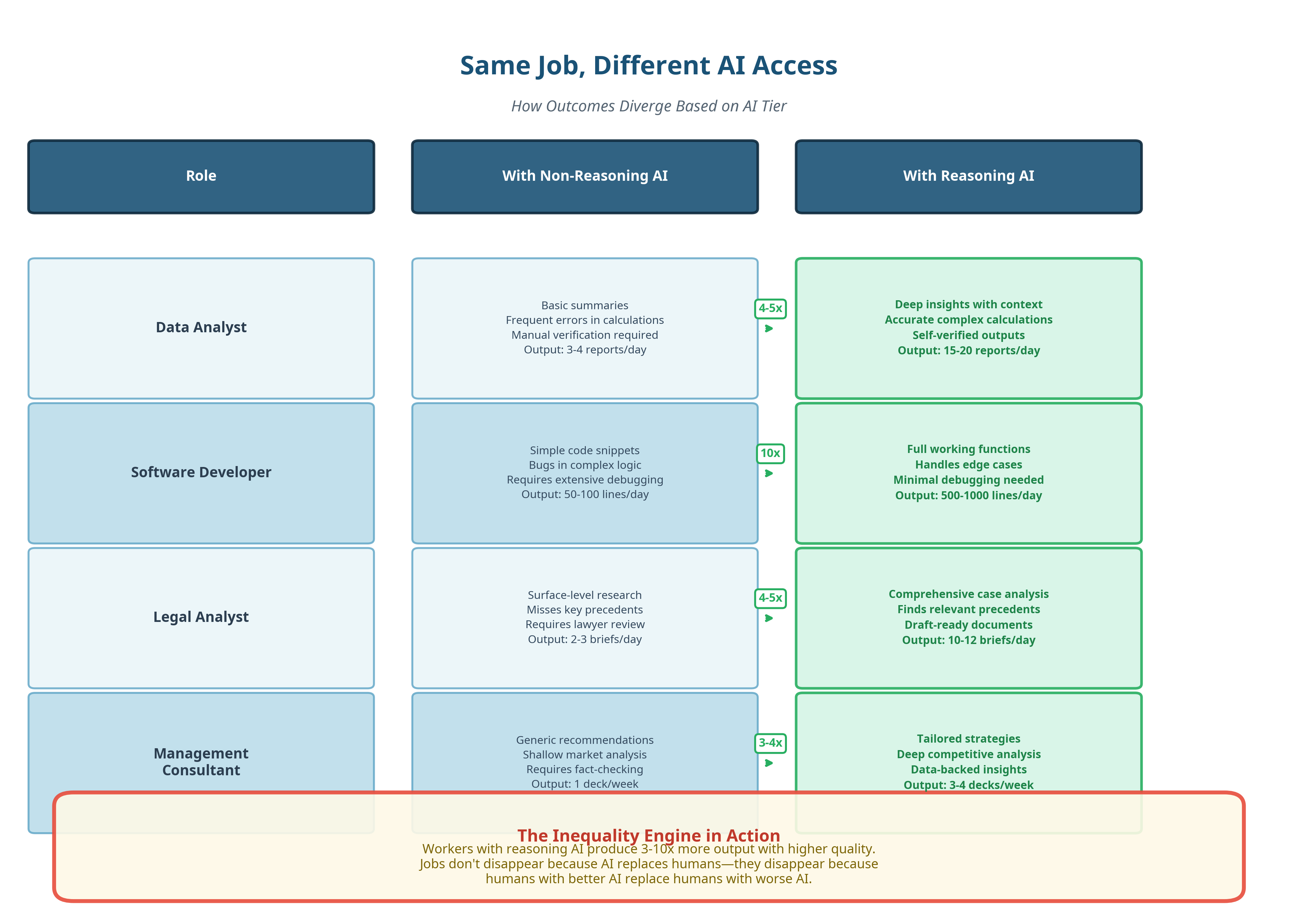

Jobs will not disappear because AI replaces humans but they disappear because humans with better AI replace humans with worse AI.

If everyone tried GPT-5.2 Pro tomorrow, the backlash would be immediate and feral.

Real AI is more than one model working alone

We call Frontier AI “models”, but really they are more like “systems”.

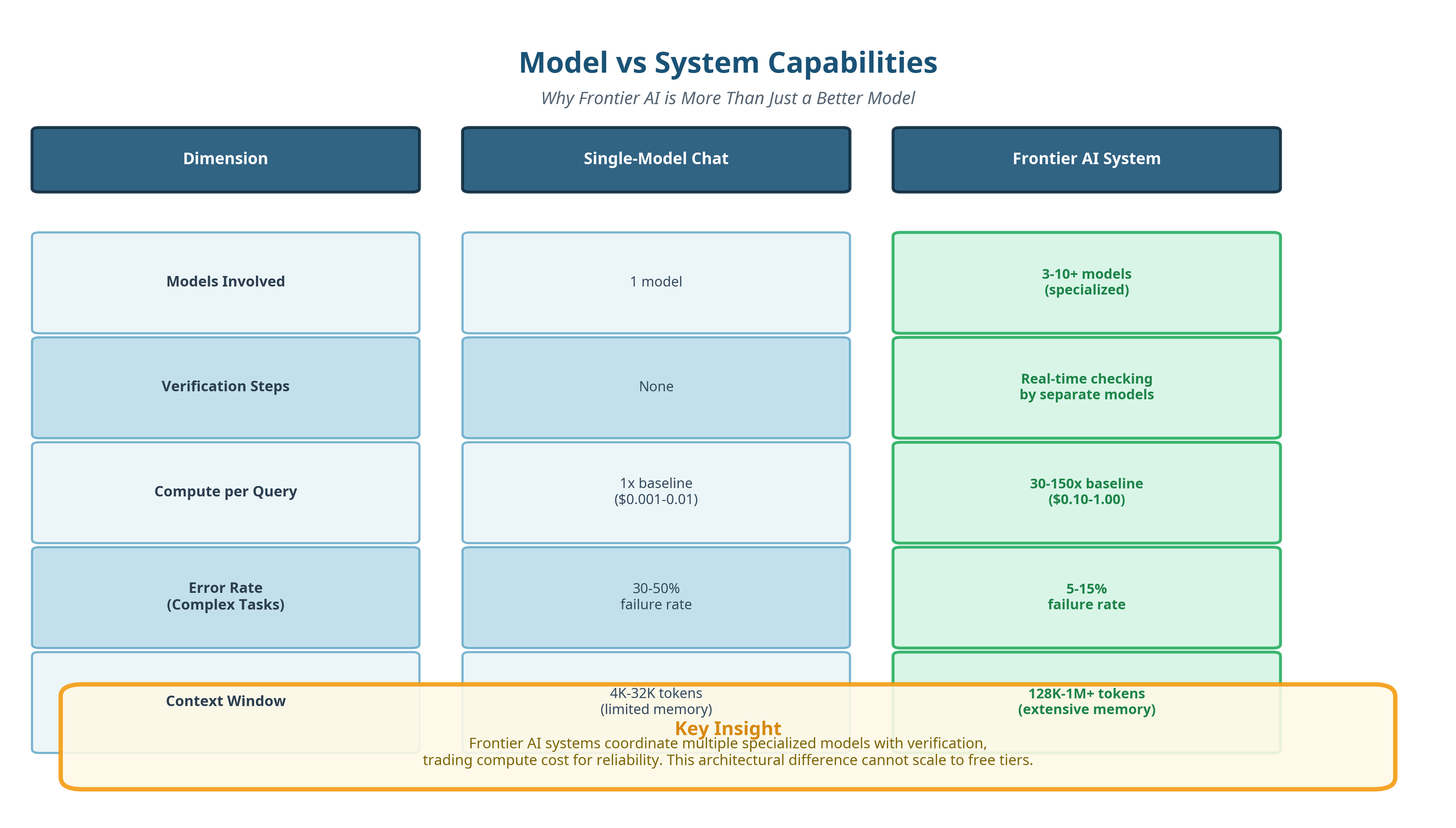

This distinction matters because most public discussion still talks about “models” as if they were single pieces of software answering prompts in isolation. That mental model is already outdated for anything at the frontier. What most people interact with today is a single model responding to a single prompt. Frontier AI systems work very differently.

They combine multiple models, verifiers, planners, and tools into a coordinated pipeline that pushes inference-time compute as far as it can reasonably go. The model you see answering is often just one part of a larger machine.

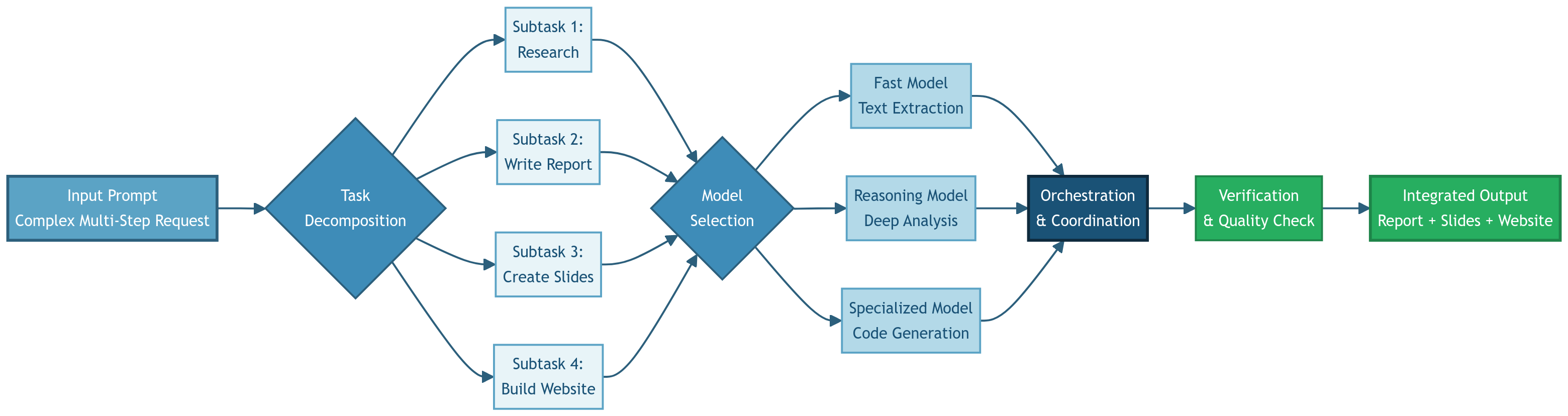

And my go-to AI, Manus, is the best example of this shift in practice right now. Manus lets you build compound prompts, multi-step instructions that chain tasks together in a single session. For example:

“Research the use of AI wide and deep, then write a report about it, then create a PowerPoint using Nano Banana that explains the concepts, and finish by building a website around it”.

Manus is not responding with a single paragraph, but it first breaks this down into a multi-stage plan. It creates an outline, sequences the tasks, and orchestrates multiple subtasks across different models, effectively acting like a project manager for collaborating models underneath.

Here’s what actually happens behind the scenes

- Manus interprets your high-level instruction and breaks it into discrete subtasks (like 1. research most relevant sources, 2. write sections of a report, 3. design slides, 4. generate code for a website).

- It then decides which classes of models are best suited for each subtask. Smaller, fast models for simple text extraction, to larger, reasoning-heavy models for deep synthesis and planning.

- Then it chains outputs together, feeding the results from one step into the next, rather than starting fresh each time.

- At the end, it organizes all of it into coherent deliverables (a written report, a slide deck, a website scaffold) with minimal human intervention (but it keeps tabs).

This is the real difference between “one prompt, one answer” interfaces and next-level systems, it’s that the AI is orchestrating, planning, and executing multi-stage workflows.

In practice, that means you can go from idea to finished product in one continuous flow, which is not done by a single model in isolation, but can only be achieved by a system that coordinates multiple models, memory layers, and task-specific engines under the hood. And that is why the scientists working at the frontier labs all agree that smaller and more specialized models – coordinated by a general language model with thinking / planning – are the future (in the LLM category).

But the thing with these systems is that they are expensive enough that AI labs often lose money serving them. That is why OpenAI positions their “Pro” model as a loss leader (well, more loss than the rest of the crew)

This is not marketing drama. It is a known industry issue. High-end subscriptions are frequently priced below true marginal cost, especially for heavy users, because companies are betting on future efficiency gains, market positioning, or enterprise spillover rather than current profitability.

Why Frontier AI costs so much

Frontier systems rely on several techniques that are mostly absent from cheaper tiers.

They use real-time verification, where separate models check the output of the primary model while it is reasoning. Verification reduces hallucinations and logical errors, but it multiplies compute usage. Every check is another model running, another pass through memory, another hit to the power bill. They use multi-agent orchestration, where one model plans the task and delegates subtasks to other specialized models. And this is especially common in research, coding, and analysis workflows, where different agents handle browsing, summarization, reasoning, and synthesis.

The benefit is robustness, and the cost is scale.

They use best-of-N sampling, where the system generates multiple solutions to the same problem and selects the most consistent or highest-scoring result. And this technique dramatically reduces variance and error rates, but it also means that you are effectively paying for several answers to get one. They use large context windows, allowing the system to hold far more information in memory while reasoning.

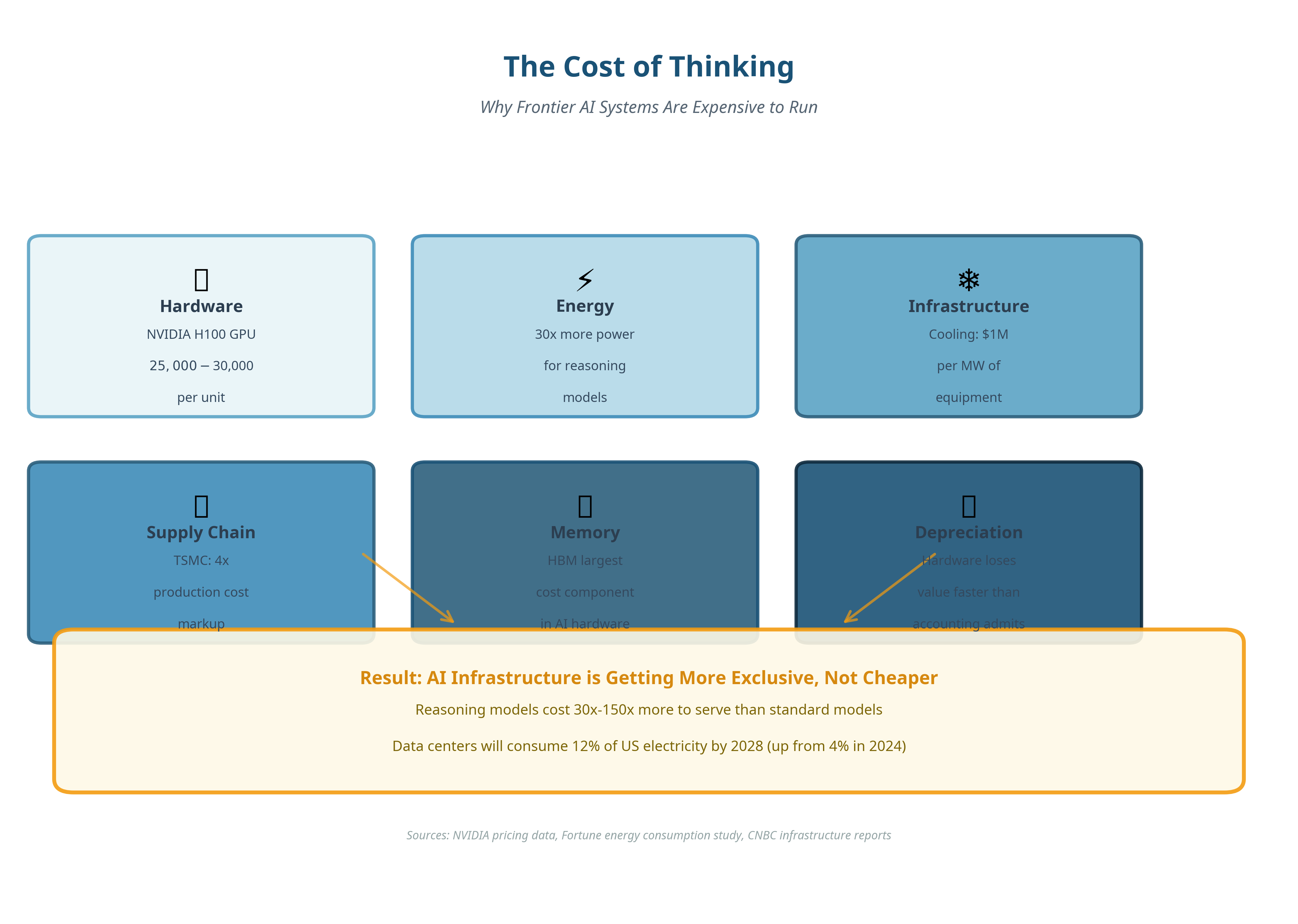

Larger context improves coherence and reduces errors caused by missing information, but memory bandwidth is one of the most expensive components in modern AI hardware.

Together, these techniques explain why frontier AI feels qualitatively different from what most people use. It is not just a better model. It is a coordinated system designed to trade money and energy for reliability.

That is also why these systems do not scale down nicely.

You cannot simply turn on verification, multi-agent planning, and best-of-N sampling for hundreds of millions of free users. The infrastructure cost would be catastrophic.

This is why the gap between free and paid tiers keeps widening. It is not just about features being withheld. It is about entire architectural approaches being economically impossible at mass scale.

Pro users drive Porches and the rest has to do with a scooter with a cracked mirror.

Will prices fall

Maybe. They shouldn’t.

This sounds counterintuitive because most technologies get cheaper over time. Software usually follows a curve where performance improves and costs drop. But the thing is that AI inference, especially at the frontier, does not follow that pattern cleanly.

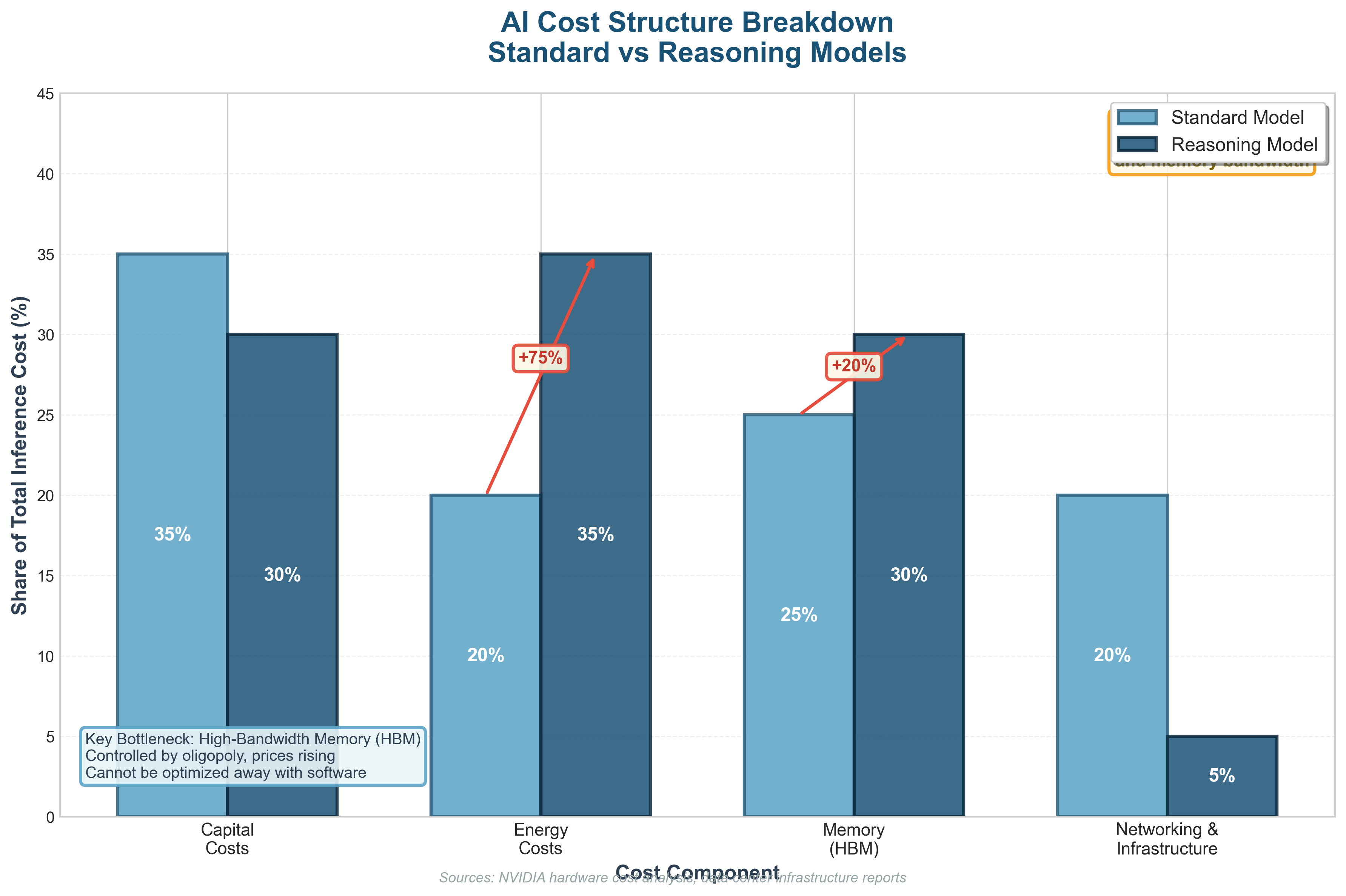

And that’s because inference workloads are inefficient. GPUs spend a large chunk of their time not computing anything useful but hauling data back and forth. Memory traffic , cache misses , synchronization overhead. That motion is not free. It absolutely murders margins..

By the way , this has a name. Low arithmetic intensity.

Low arithmetic intensity means performance is limited by memory bandwidth rather than raw compute, and throwing more chips at the problem does not linearly reduce cost.

Hardware makes this worse. It depreciates at a pace that makes accountants sweat. High-end AI accelerators have short economic lifespans. New generations arrive fast, benchmarks leapfrog each other, and suddenly last year’s flagship becomes a very expensive space heater long before it stops functioning. NVIDIA can charge roughly four times production cost for its accelerators because demand is desperate (not because the economics are elegant). And also memory prices keep climbing. High-Bandwidth Memory is already the largest line item in modern AI hardware bills of materials.

HBM (High Bandwidth Memory) is essential for reasoning-heavy workloads , and supply is controlled by a very small club of manufacturers. That creates structural upward pressure on prices that software efficiency alone cannot undo. You cannot refactor your way out of physics.

And moreover, the supply chains are highly concentrated. TSMC sets terms for advanced chip manufacturing. Memory vendors operate as an oligopoly. Prices rise.

And then there is ASML who the industry never puts in their PowerPoints. They are always sitting at the choke point like a polite Dutch bouncer. Every advanced chip depends on extreme ultraviolet lithography, and ASML is effectively the only company that can build those machines. Each one costs north of 200 million euros and takes years to assemble, and contains more engineering than most national infrastructure projects. TSMC needs ASML. NVIDIA needs TSMC. Everyone waits their turn, and the thing with prices is they do not politely drift downward in a queue like that.

AI infrastructure is not getting cheaper, but instead getting more exclusive.

So what now

AI is becoming pay-to-win.

And it’s not because anyone explicitly decided this should be the case, but simply that the strongest performance gains are tied directly to resources that do not scale democratically like compute, energy, and capital.

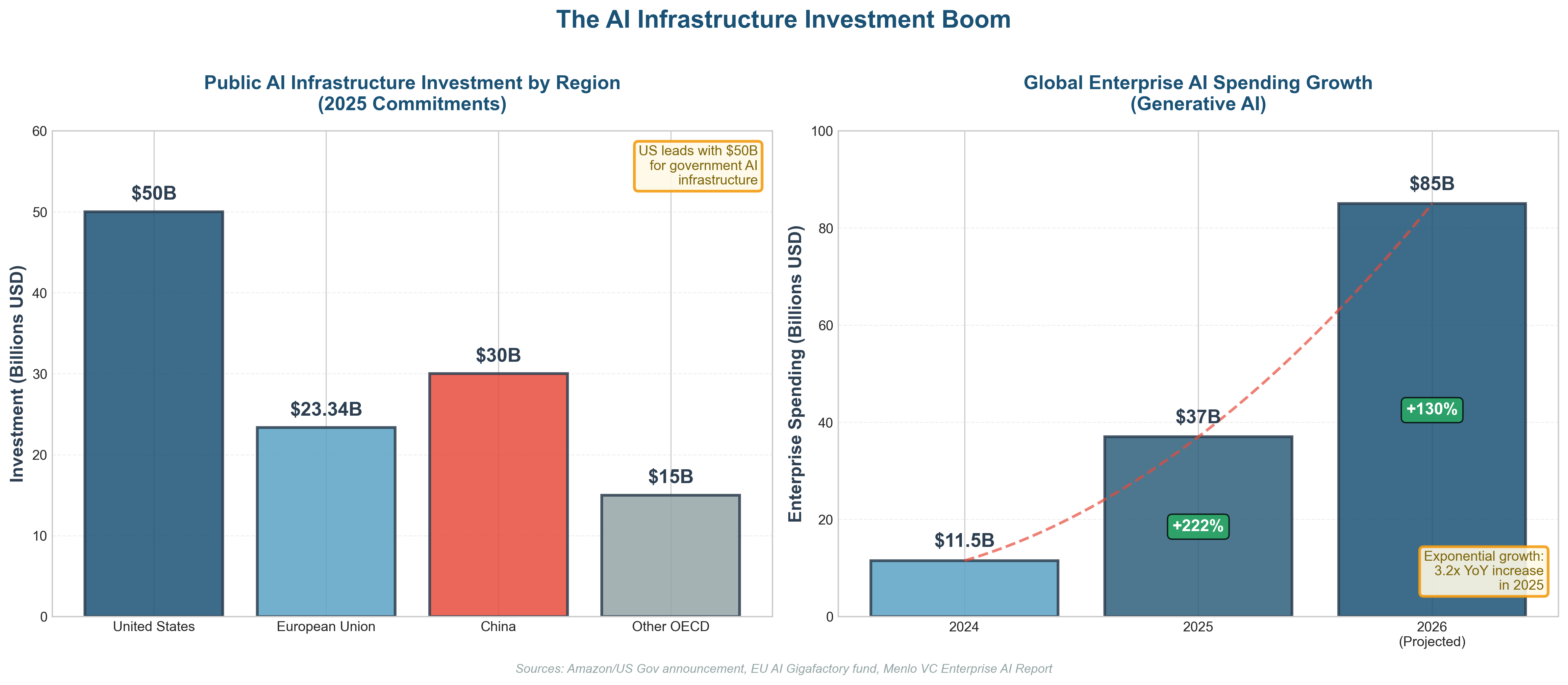

But governments could still intervene to prevent this AI divide.

They could ease power constraints, and they could support alternative hardware players. They could even invest in public compute infrastructure instead of only regulating private deployments.

Most importantly, they could back open-source instead of quietly strangling it.

Open-source models have repeatedly forced price competition and capability diffusion. This is not ideological. It is observable in both Western and Chinese ecosystems. Nothing has lowered AI prices faster than Chinese open-source models. That is just reality.

If Western governments intervene, they should demand open models in return for subsidies, power access, or infrastructure support. Otherwise, subscriptions will creep from $200 to $2,000 per month.

And intelligence will stratify into two classes.

Those who can afford to think better.

And those who can’t.

This is where the difference between the EU and the US actually matters.

The US approach is simple and brutally consistent. Let private capital run as fast as possible. Accept concentration as the price of speed. Regulate later, lightly, and usually after the winners are already entrenched. Intelligence becomes a product. Access becomes a subscription. Sovereignty becomes a talking point.

The market decides who gets to think at scale.

Europe, for all its flaws, is experimenting with a different lever. Instead of assuming hyperscalers will benevolently solve everything, the EU is starting to treat compute as infrastructure. Publicly funded supercomputers. National and cross-border AI compute facilities. Investments in sovereign cloud, energy capacity, and shared research platforms.

Not to replace the private sector but to counterbalance it.

Public compute make sure that universities, public services, startups, and critical industries are not permanently locked out of advanced capabilities by price alone. It retains a minimum level of cognitive capacity inside the public sphere.

And that difference matters a lot if you want to close that divide.

Because once intelligence is fully privatized, every policy discussion becomes hypothetical. You cannot regulate systems you cannot afford to run. You cannot audit models you cannot access. You cannot innovate if the entry fee is a seven-figure cloud contract.

The EU is late, underpowered, and still arguing with itself. But at least it is pulling on the right thread.

The US is betting that focus on AGI plus full privatization and competition will somehow sort itself out.

But history suggests otherwise.

This is no longer about who builds the best models.

It is about who gets to use them.

Signing off,

Marco

I build AI by day and warn about it by night. I call it job security. Big Tech keeps inflating its promises, and I just bring the pins and clean up the mess.

👉 Think a friend would enjoy this too? Share the newsletter and let them join the conversation. LinkedIn, Google and the AI engines appreciates your likes by making my articles available to more readers.

To keep you doomscrolling 👇

- I may have found a solution to Vibe Coding’s technical debt problem | LinkedIn

- Shadow AI isn’t rebellion it’s office survival | LinkedIn

- Macrohard is Musk’s middle finger to Microsoft | LinkedIn

- We are in the midst of an incremental apocalypse and only the 1% are prepared | LinkedIn

- Did ChatGPT actually steal your job? (Including job risk-assessment tool) | LinkedIn

- Living in the post-human economy | LinkedIn

- Vibe Coding is gonna spawn the most braindead software generation ever | LinkedIn

- Workslop is the new office plague | LinkedIn

- The funniest comments ever left in source code | LinkedIn

- The Sloppiverse is here, and what are the consequences for writing and speaking? | LinkedIn

- OpenAI finally confesses their bots are chronic liars | LinkedIn

- Money, the final frontier. . . | LinkedIn

- Kickstarter exposed. The ultimate honeytrap for investors | LinkedIn

- China’s AI+ plan and the Manus middle finger | LinkedIn

- Autopsy of an algorithm – Is building an audience still worth it these days? | LinkedIn

- AI is screwing with your résumé and you’re letting it happen | LinkedIn

- Oops! I did it again. . . | LinkedIn

- Palantir turns your life into a spreadsheet | LinkedIn

- Another nail in the coffin – AI’s not ‘reasoning’ at all | LinkedIn

- How AI went from miracle to bubble. An interactive timeline | LinkedIn

- The day vibe coding jobs got real and half the dev world cried into their keyboards | LinkedIn

- The Buy Now – Cry Later company learns about karma | LinkedIn

Leave a comment