Humans and their brains, man, what a combination. That soggy three-pound cauliflower in our skulls that hoards our water, guzzles glucose like it’s for free, and drains 20 percent of our total energy budget just so that we’re all able to narrate our misery in high definition. The rest of the body just tries to survive like a federal employee under DOGE, while the brain lounges in its velvet throne, demanding metabolic tribute for the privilege of generating intrusive thoughts and forgetting everybody’s birthdays.

And to make things worse, at some point we became “conscious”, though nobody knows why or who approved that feature rollout. Honestly, half the time it feels like consciousness was an experimental patch pushed at a Friday afternoon at 17:00 by an intoxicated cosmic engineer at Cloudflare, and somehow it shipped to production. And sure, once in a while it helps, like when there’s a tiger in the woods, but mostly it’s a luxury item that backfires, like giving a raccoon a credit card.

Now, the thing with consciousness is that it came with some shabby abstract mental models that are stitched together from childhood mistakes and misremembered science documentaries. These patchwork representations help us pretend that we understand the world, even though we can barely track our own car keys. Yet we rely on these models to dodge disasters, and make choices that won’t embarrass us in public.

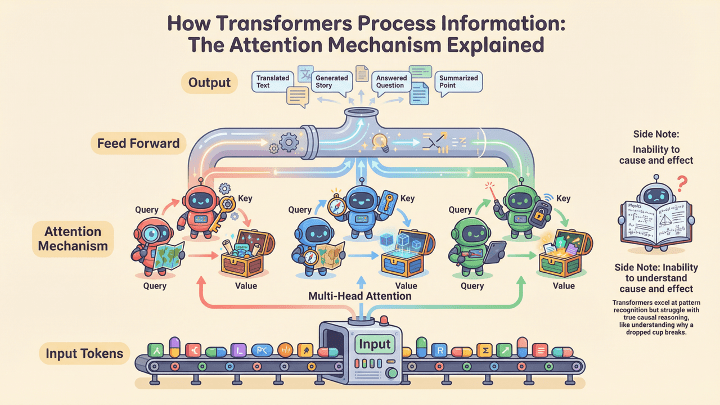

And for a while, we all thought we had invented the digital version of this mental peepshow in the form of the transformer architecture that led us to the Generative AI boom.

Oh, the honeymoon period felt so nice. We fed our little Oompa Loompas some text and images, and it fed us deepfake porn back, and then the whole planet clapped like circus seals because autocomplete suddenly had pimp-like swagger. Every VC on earth wanted to bet their money on the AI that led to “AGI”, despite the fact that transformers can’t keep a grocery list consistent across three sentences. So the frontier guys tried to scale it beyond big – up to 670 billion parameters at DeepSeek – and so we all ended up with chatbots that hallucinate court cases, images of the pope in a puffer jacket, Stephen Hawkins doing tricks at the skatepark, and enough other fake celebrity content to traumatize entire fandoms.

But scientists saw the cracks, the brittle reasoning, the lack of memory, and the attention mechanism that was panting like an asthmatic pug (dog) when sequences got long. Eventually the researchers looked at transformers the way you look at a colleague who leaves raw chicken on the counter.

AGI actually never had a freakin’ chance. Not with that architecture it wouldn’t anyway. Not with that compute bill. And certainly not with that level of confusion.

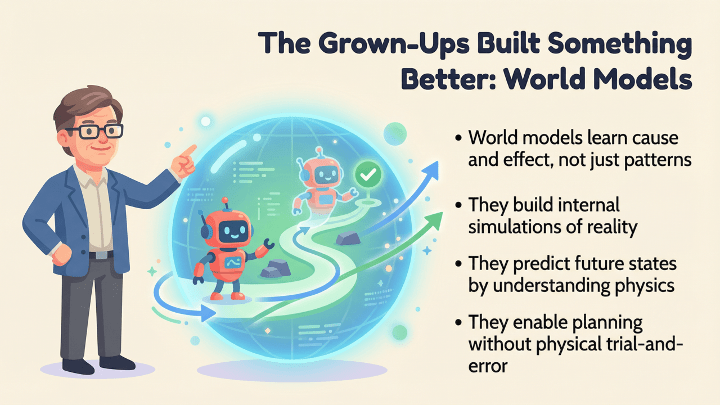

So the grown-ups in the field did what grown-ups always do when the children are distracted by fancy new nonsense. They simply started building something better. Something predictive of course, certainly something grounded, and absolutely something that doesn’t fold like my will to work on a cold and dark Monday morning the moment you ask it to do physics or long-term planning.

And they delivered.

More rants after the messages:

- Connect with me on Linkedin 🙏

- Subscribe to TechTonic Shifts to get your daily dose of tech 📰

- Please comment, like or clap the article. Whatever you fancy.

Hello World!

World models in AI aim for the same trick, but without the emotional baggage and neuroses. Large Language models learn through real-world trial and flaming error, but with World Models, we let it build an internal simulation (of the world). It’s a private sandbox where it can imagine futures, and plan without destroying physical property or running up a compute bill that makes the CFO sweat through his linen shirt.

This approach saves ridiculous amounts of energy and training time. It also pushes AI closer to how we as humans operate – predicting , imagining , simulating , calculating , hallucinating – minus the panic attacks. Yann LeCun (the papa of deep learning, the guy who invented a neural network, ex Chief at Meta, and above all an AGI skeptic), he keeps reminding everyone that world models are a prerequisite for human-level intelligence and that it’ll take about a decade to get there, assuming we stop being idiots long enough to finish the damn work.

Right now we’re still dealing with early prototypes of these models, endearing and deranged in equal measure, and they’re learning physics through dreams and chaos. And if we actually want breakthroughs instead of only press releases, we need to understand how these systems work, what they can do, and what fresh disasters they’ll inspire next.

So let us begin the grand tour of world models, the synthetic brains that might finally outgrow the dysfunctional meat engines that inspired them.

The part where I pretend to understand things

Back in the 90s, when computers were beige, modems made noises like a cat being flattened by a steam roller, and responsible adults thought Solitaire counted as a productivity tool, this guy Richard S. Sutton introduced the Dyna algorithm. It was model-based reinforcement learning before that phrase made venture capitalists salivate. Dyna had three jobs – learn the world, plan inside that world, and react to the world (without hyperventilating).

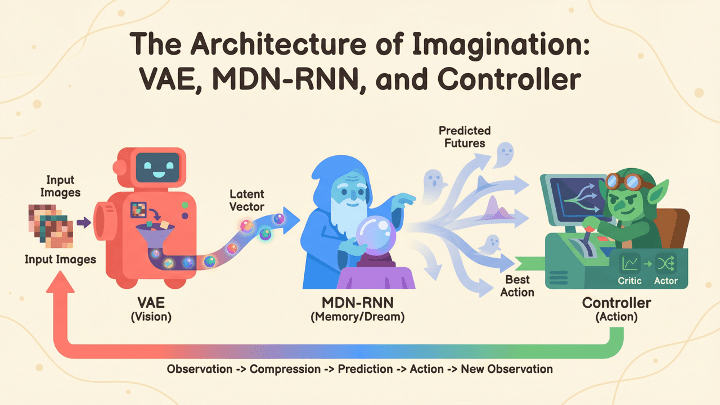

In 2018, David Ha and Jürgen Schmidhuber (not a pseudonym) wrote the “World Models” paper, in which they showed that you could slap a VAE, an MDN-RNN, and a controller together and get an agent that learns by dreaming. And if you don’t get those acronyms, don’t worry, you’re normal. A VAE is just a probabilistic compressor, it squashes images etc. into neat little vectors so that the agent doesn’t spend ten million billion GPU hours staring at pixels like my Weiner does when he gives me the side-eye, it reduces the world into a something small, the MDN-RNN can digest. An MDN-RNN is basically a squirmy little fortune-teller that tries to guess the next moment in time by spitting out a bunch of possible futures instead of committing to one (like my ex always did). And the controller is that tiny gremlin sitting on top of the whole thing, poking the system into taking actions and acting like it’s the boss.

Together they form a kind of budget-friendly subconscious where the AI agent takes hallucinogenic shrooms, and strolls through its own latent space, learns imaginary physics, and then wakes up acting like it discovered the secrets of the universe. It is truly adorable, if you ignore the part where it sometimes outperforms humans who presumably exist in the real world.

And that paper became the moment everyone realized that – oh , shit, maybe models don’t need reality to learn. Which, ironically, puts them one step ahead of half the people I’ve worked with.

I remember looking at that architecture back when it was released, thinking – wonderful, the machines have imagination now, and I still can’t assemble a bookshelf without consulting YouTube.

The trick for me now, is to try to write it down in a way that will make you go “Ah, I get it now”. So, let’s give it a shot, shall we?

It starts with how they learn about their place in the world.

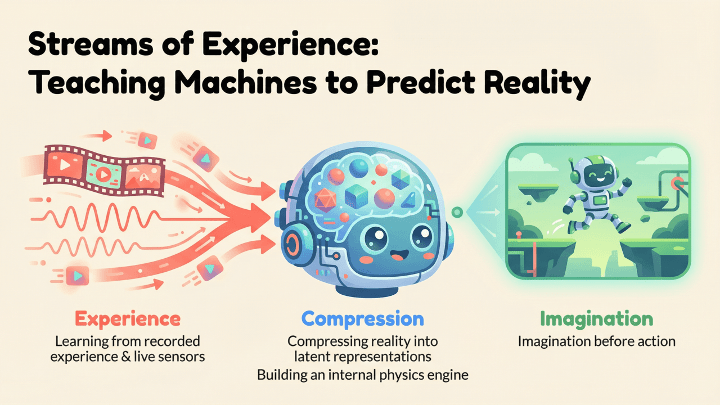

World models learn by watching the world and then predicting what will happen next. That’s the entire trick. You give them streams of experience, that could be a robot moving through a room and seeing how objects shift in its camera feed as it steps forward. It could be a drone recording how the horizon tilts when a gust of wind hits it. It could be a self-driving car watching the pattern of brake lights ripple through traffic during rush hour. It could even be a simulated agent playing thousands of episodes of a game, learning that every action nudges the world into its next state.

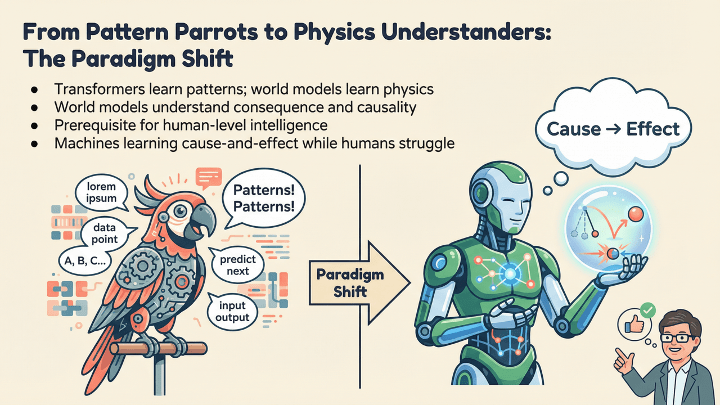

These streams are simply moments connected to other moments – frame after frame of cause and effect. For instance, a cup falling from a table or a Weiner dog running through a doorway. Anything that shows how the world changes is food for a world model. And that is exactly the difference in learning between our current AI and world models. It learns cause and effect, whereas the popular models of today learn only to recognize objects.

That’s what “streams of experience” really are. They are long, continuous slices of reality that teach the machine what tends to happen next. And the more of these it sees, the better its internal simulation becomes.

And then they squeeze that reality down into a compact internal movie where they replay those events, and learn the physics of cause and effect.

A world model can learn in two ways. The first is the classic AI route where you feed it mountains of recorded experience. An LLM gets fed corpuses of text, but a world model gulps down sequences of video frames, or robot trajectories, gameplay recordings, physics simulations, and anything that shows how one moment becomes the next. Show it enough examples of a ball bouncing, a robot walking, a drone drifting in the wind, and it will slowly pick up the rules hiding underneath those motions.

The second way it learns is more resembling life itself, the model can learn directly from sensors. A robot looks through a camera, feels its joints move, listens through microphones, measures how it tilts or falls through an IMU, and senses contact through pressure pads. Every wobble, slip, collision, stumble, and course correction becomes fuel for the world model. Each tiny sensory update teaches it what leads to what. It starts to understand that if its leg pushes this way, it will tilt, so, if the environment shifts, its predictions must shift too.

World models use a blend of both.

They begin life by binge-watching massive datasets, then refine themselves by exploring the real world through sensors, seeing how their predictions match the messy truth.

The model no longer needs to act blindly. Before taking a step, it imagines the step. Before moving an arm, it simulates the movement. Before navigating a space, it rehearses ten possible futures in its head and picks the best one.

LLMs learn to speak a language. Vision models learn images. But world models learn reality itself. They learn how things move, fall, collide, bend, persist, break, and recover. They learn the grammar of physics the same way you once learned not to touch a hot stove. And once they have enough experience, they begin to run their own internal world of predicting, visualizing, reasoning, long before they ever lift a finger or fire a motor.

That’s the heart of it.

And yes, my dear well above-average intelligent friend, the sad part is that your robot vacuum already has a cleaner understanding of household physics than most humans have of their own lives.

The big four trying to steal prometheus’ job

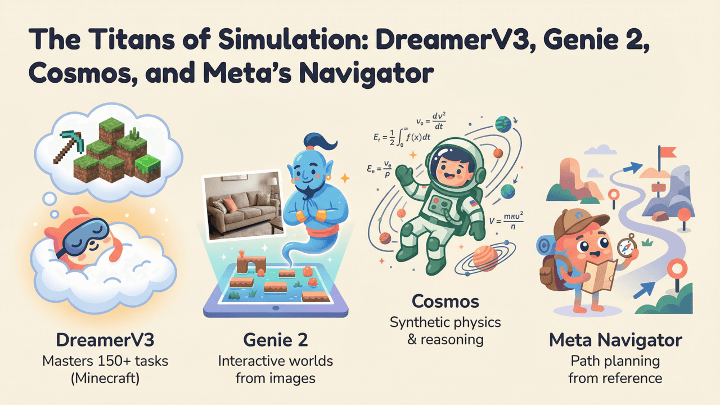

DreamerV3 from DeepMind is the classic world model who masters 150 tasks while you still struggle to remember your email password. It compresses the world into latent states and simulates futures, evaluates them with a critic, and acts with an actor. It uses KL divergence† and imagines entire Minecraft timelines without touching a block in reality.

Genie 2 is another model that builds interactive environments from a single image prompt. Take a picture of a couch, and boom, now it’s a virtual obstacle course.

Then there’s NVIDIA’s Cosmos World Foundation Models that are active in synthetic physics. Cosmos-Predict1 simulates temporal video evolution, Cosmos-Transfer1 adds control, Cosmos-Reason1 stitches in explanatory language using a Mamba-MLP-Transformer chimera.

And let’s not forget Meta’s Navigation World Model that calculates navigation paths from a single reference image. It uses Conditional Diffusion Transformers to hallucinate entire routes.

A good way to understand how a world model works is to imagine a small robot trying to learn how to walk.

At first, it knows nothing.

It doesn’t know what its legs are, or what the floor is, or why gravity is such an awkward experience. So it starts by collecting experiences through camera frames of the room, IMU readings telling it when it tilts, joint sensors reporting which motor moved where, and little collisions that teach it the floor is closer than expected. Every wobbly step gives the model a chain of “before and after” cause-and-effect moments. The robot moves its leg, feels itself tipping, the camera shows the horizon tilting, the IMU beeps internally, and the world model ingests this sequence as raw reality. Then it compresses all those chaotic inputs into a tight, abstract representation (a latent state as it is called), small enough to simulate quickly but rich enough to preserve the physics that matter.

And after seeing thousands of these sequences, the world model starts predicting what will happen next, if the robot shifts its weight this way it will fall, if it adjusts torque on the opposite leg it will recover. At some point the robot doesn’t need to experiment in the real world every time no more, because it simply imagines the next step inside its head, checks whether that imaginary step ends in a faceplant, and picks the best option.

The model has learned its own internal physics engine. And that is exactly like our kids learn. And here you see that all the new models that are being developed and piloted, are closely resembling the human brain, and it’s cognitive paths.

This is the essence of a world model. It builds a miniature version of reality inside itself (the “word model”) which 9is constantly updated. It’s an internal simulator that lets the machine think ahead rather than react blindly. And the more experience it ingests, the better it becomes. Where an LLM learns how sentences fit together, a world model learns how reality fits together.

Now put this machinery into massive compute clusters, feed it millions of trajectories from robots, game engines, autonomous systems, and synthetic video, and you get the new brains of our artificial future.

† KL divergence measures how far your model’s predicted probability distribution drifts from the real one, and it quantifies how wrong it is.

The part where I mansplain why this matters

World models are not a research thing nor a cute little extension to transformers. A world model does not parrot patterns, but it starts to understand the physical, continuous world and the entropy associated with it. The world we actually live in. They give machines a sense of consequence, prediction, and internal rehearsal, the same cognitive superpowers our greedy little brains developed over millions of years.

Transformers – the architecture of our current AI play thingies – were build for the era where models talk about the world, but world models are built for the era of machines that internalize it.

So, the next decade of breakthroughs will not be about infinitely scaling text models to the size of Jupiter, but they will come from giving AI a world to imagine – and the ability to imagine it correctly.

And yes, the irony is delicious, the machines finally learn cause and effect, while half of humanity still hasn’t.

Signing off,

Marco

I build AI by day and warn about it by night. I call it job security. Big Tech keeps inflating its promises, and I just bring the pins and clean up the mess.

👉 Think a friend would enjoy this too? Share the newsletter and let them join the conversation. LinkedIn, Google and the AI engines appreciates your likes by making my articles available to more readers.

To keep you doomscrolling 👇

- I may have found a solution to Vibe Coding’s technical debt problem | LinkedIn

- Shadow AI isn’t rebellion it’s office survival | LinkedIn

- Macrohard is Musk’s middle finger to Microsoft | LinkedIn

- We are in the midst of an incremental apocalypse and only the 1% are prepared | LinkedIn

- Did ChatGPT actually steal your job? (Including job risk-assessment tool) | LinkedIn

- Living in the post-human economy | LinkedIn

- Vibe Coding is gonna spawn the most braindead software generation ever | LinkedIn

- Workslop is the new office plague | LinkedIn

- The funniest comments ever left in source code | LinkedIn

- The Sloppiverse is here, and what are the consequences for writing and speaking? | LinkedIn

- OpenAI finally confesses their bots are chronic liars | LinkedIn

- Money, the final frontier. . . | LinkedIn

- Kickstarter exposed. The ultimate honeytrap for investors | LinkedIn

- China’s AI+ plan and the Manus middle finger | LinkedIn

- Autopsy of an algorithm – Is building an audience still worth it these days? | LinkedIn

- AI is screwing with your résumé and you’re letting it happen | LinkedIn

- Oops! I did it again. . . | LinkedIn

- Palantir turns your life into a spreadsheet | LinkedIn

- Another nail in the coffin – AI’s not ‘reasoning’ at all | LinkedIn

- How AI went from miracle to bubble. An interactive timeline | LinkedIn

- The day vibe coding jobs got real and half the dev world cried into their keyboards | LinkedIn

- The Buy Now – Cry Later company learns about karma | LinkedIn

Leave a comment